A tiny, bread loaf-sized communications satellite built by a startup with roots in U of T Engineering spent the weekend quietly zipping over the heads of unwitting Torontonians — and there’s likely many more to come.

Kepler Communications, founded by Mina Mitry (EngSci 1T2, AeroE MASc 1T4) and Jeffrey Osborne (AeroE PhD candidate), said its first nanosatellite was successfully deployed by a rocket that launched on Jan. 19 from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in northwestern China. At an altitude of about 552 km, the satellite’s polar orbit takes it over Kepler’s home base in Toronto twice in the morning and two more times in the evening.

The launch — touted as a first for a commercial communications satellite operating in low earth orbit on a frequency known as the Ku-band — is an important first step toward Kepler’s goal of providing low-cost data communications for connected devices on Earth and beyond.

But, for now, Kepler’s founders are just revelling in their accomplishment.

“The company began two years ago with a conversation at the bar,” says Osborne. “So you get a little awe-inspired when you actually put something in orbit. That’s pretty cool.”

The startup uses two ground-based stations to communicate with its inaugural satellite. One is located in Markham, Ont., and handles telemetry and tracking. The other is in Inuvik, N.W.T., and handles the satellite’s payload communications.

Initially, the satellite will use the high-frequency Ku-band to inexpensively transmit large quantities of non-time sensitive data for a handful of customers. With only one satellite, Kepler is not equipped to offer real-time communications links.

“You’re thinking of things like an offshore oil and gas platform that wants to move terabytes of environmental or GIS data, or CCTV camera footage,” Osborne says. “They can send a lot of data and do it really cheaply – and we can provide a global service.”

The decision to use the high frequency Ku-band was a deliberate choice. Though it presented Kepler with some key engineering hurdles, it’s capable of handling a lot of data and allowed Kepler to build its affordable nanosatellites with smaller components, Osborne says.

Osborne and other members of Kepler’s 15-person team, tracked the rocket launch through WhatsApp messages from Mitry, who travelled to China to witness the event first-hand.

“We are really excited that we are the first to deploy a commercial Ku-band [low-earth-orbit] spacecraft,” Mitry said in a press release issued by the startup.

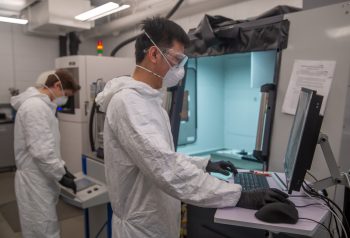

The road to last week’s launch began at U of T’s Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering. Kepler’s co-founders, including Wen Cheng Chong (EngSci 1T3) and Mark Michael (ECE PhD candidate), also leaned on the services of several U of T entrepreneurship hubs, including The Entrepreneurship Hatchery, the Creative Destruction Lab and Start@UTIAS, which is affiliated with the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies. The team took home the $20,000 grand prize at the Hatchery’s Demo Day competition in 2015.

The plan is to eventually launch dozens more of the tiny satellites to form a constellation that will help transmit the vast quantities of data needed to realize the Internet of Things, a term that refers to millions of interconnected machines, devices and sensors.

Kepler says it foresees commercial opportunities helping companies to track assets like railcars, shipping containers or construction equipment. It could also provide the linkages necessary to enable the deployment of remote soil moisture sensors or seismic monitors.

“As the need for connectivity increases, we increase our constellation capacity in tandem,” Mitry said in a statement. “It’s how we believe we can sustainably deploy a [low-earth-orbit] constellation.”

While Kepler’s current focus is using space satellites to cheaply connect things back here on Earth, Osborne says the long-term vision is to seed a new “space economy” by enabling connections between space-based equipment and vehicles.

“We have fundamental belief that infrastructure spurs development,” he says.