A multidisciplinary team is looking at the possibility of using the omnipresence of smartphones to monitor certain aspects of mental health.

By recording short bursts of ambient noise and mapping that audio over time, the team found that keeping a regular daily routine was negatively correlated with subjects self-reporting a symptom of depression.

The team is led by Daniel Di Matteo (ECE PhD candidate), and supervised by Professor Jonathan Rose (ECE) and psychiatrist Dr. Martin Katzman. Their new app turns on a smartphone’s mic for 15 seconds every 5 minutes. The team installed the app on the phones of 112 volunteer subjects to record ambient noise over a two-week period.

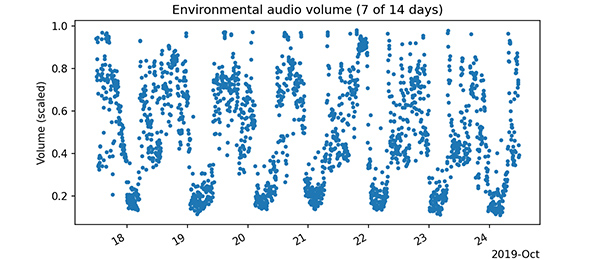

The team then extracted the average volume of noise for short, discrete durations. When plotted over time, this volume data has peaks and troughs like a wave whose regularity can be quantified. To achieve a measurement of regularity this way, by means of ambient noise, has not been done before.

“It’s well known — though not perfectly understood — that there’s a connection between mental health and regularity in your days,” says Di Matteo.

“This regularity measurement is a statistic, like blood pressure might be in a medical study,” he adds. “We looked for a relationship between this statistic and the subject’s mental health questionnaire scores.”

The findings of this explorative study, the first of three, were published in August 2020 in the medical and health research journal JMIR.

The driving force behind the research is to gather and objectively process passive, continuous data to compare alongside a broad range of symptoms from social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, depression and general impairment.

“Consider how mental health monitoring currently works,” says Rose. “Patients visit their therapist every week or so by going to a clinic or office. The patient chooses how to present themselves and the therapist interprets what they hear.”

But with a smartphone in every backpack, pocket or purse these days, there’s an opportunity to gather data far more frequently. Because intermittent recording goes unnoticed, the data-gathering is passive, too: the act of measuring isn’t changing what’s being measured.

One of the challenges for an observational study like this — as with many similar studies in this field — is managing privacy protections.

The research ethics board set limitations on how the team could use the audio. They couldn’t listen to it, nor could they keep it for longer than a few weeks; any discernible words had to be stored in isolation so that the original conversation couldn’t be recreated.

It has long been known that the presence/absence of voices is associated with depression. A second study, currently in review, considers this word-based data, while a third will look at the predictive potential of a robust app that includes data for location, on/off screen activity and motion detection.

If it’s possible to build a medical model of mental health, based only on smartphone data, the innovation could be a valuable asset for the field.

“When someone’s going into depression they just kind of fade away,” says Rose. “Imagine an app with the capability to notify a spouse or a parent when this happens. Imagine one that could more finely track the efficacy of a prescription.”

His imagination — and research — has been fired up by such scenarios for seven years since the inception of The Centre for Automation in Medicine and his collaboration with Dr. Martin Katzman and fellow researchers at the S.T.A.R.T. Clinic.

“It’s a true partnership,” says Rose of his research partners in the clinic. “They learn what’s possible with machine learning while we learn aspects of psychiatry and statistics. We don’t just do what they tell us.”

He adds with a smile, “That goes both ways, of course.”