As hospital emergency wait times continue to increase in Canada, Professor Goldie Nejat (MIE) believes machine intelligence and robotics can play a key role in easing the strain by streamlining the delivery of health care.

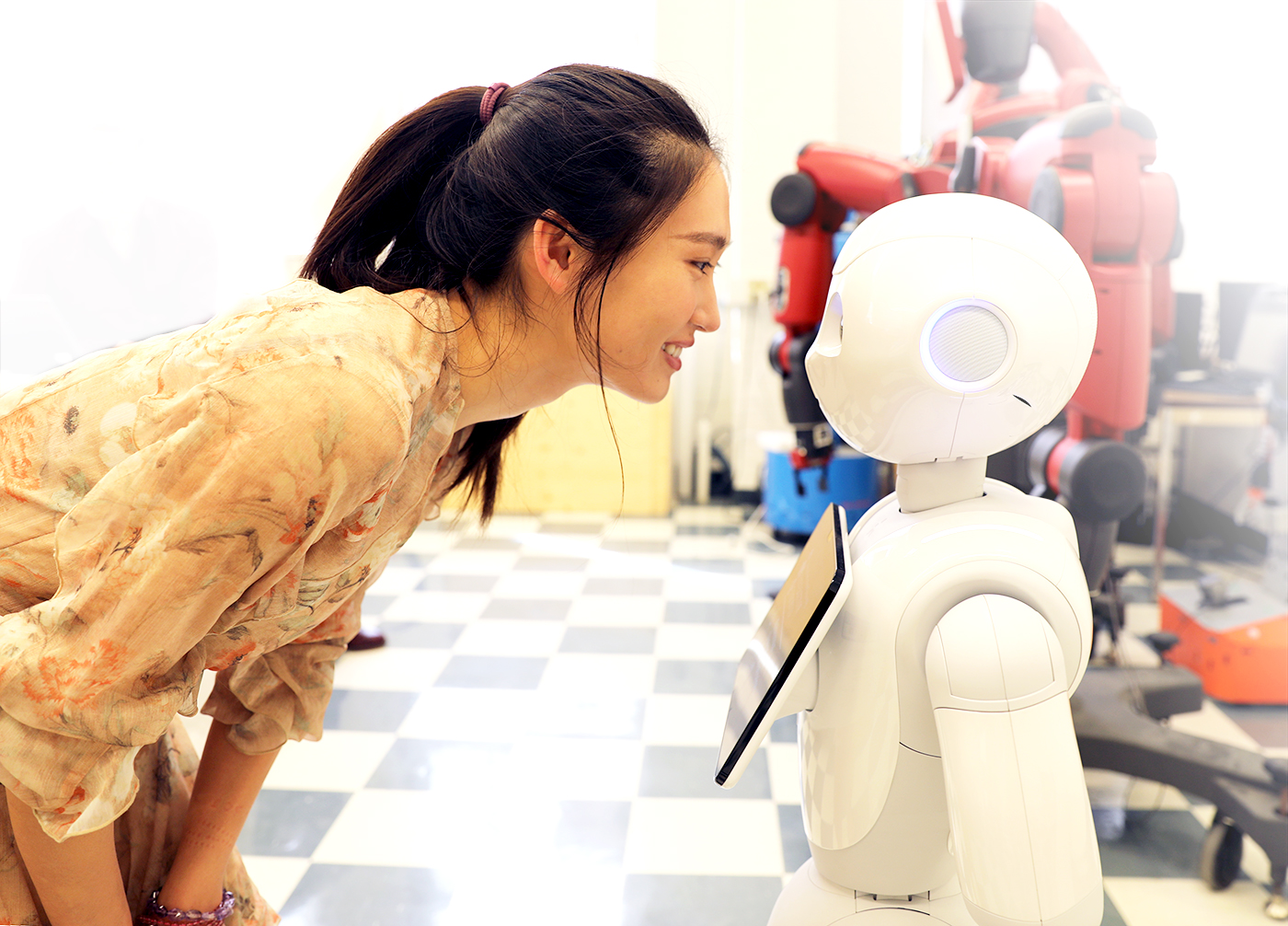

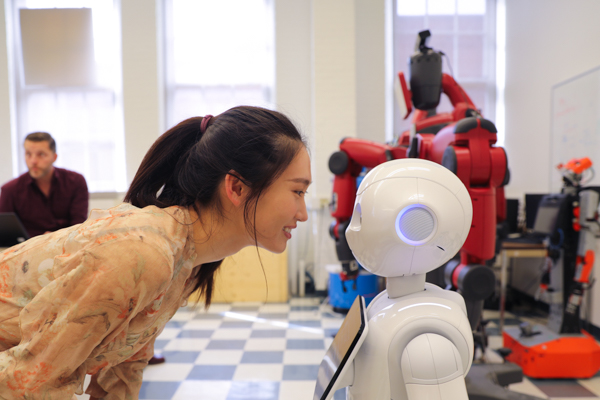

In July, two identical semi-humanoid robots named Pepper arrived in Nejat’s Autonomous Systems and Biomechatronics Lab. Standing about four feet high, each Pepper is equipped with four microphones, two HD cameras and a 3D depth sensor, all of which enable the robot to detect and respond to voices and body language. The programmable robotic platform is manufactured by SoftBank Robotics.

Nejat and her team are now working to design Pepper’s ‘brain’ — the algorithms that govern how the robot will interact with humans. Their ultimate goal is to deploy Peppers in hospital settings to help minimize emergency wait times by automating data intake, monitoring the conditions of patients and providing companionship in hospital rooms.

Nejat envisions Pepper as an interactive go-between for patients and health-care professionals. In waiting rooms, the robot can gather information about why the patient is there and the priority of the patient based on symptoms. It can then send that information to the nurse’s station, and update it as necessary.

“A lot of information needs to be given before a patient is seen by a doctor or specialist,” says Nejat, who is also the director of U of T Engineering’s Institute for Robotics & Mechatronics (IRM). “We’re trying to have robots help with that.”

Once the patient is admitted, Pepper will provide monitoring assistance, minimizing possible delays for any patients in need of assistance. “If something urgent has happened, the robot can alert the nurse’s station, even before the patient presses the button to indicate they need help,” says Nejat.

Pepper could also provide companionship and guide patients through daily activities, such as taking medication or doing rehabilitation exercises.

“Sometimes it’s good to just have a robot there for companionship, especially for patients who are by themselves,” added Nejat. “This could be children whose parents are working during the day, or older adults whose families only visit at certain times.”

To do this, the researchers will need to design Pepper’s artificial intelligence to gather not only information, but a sense of how patients are feeling, what Nejat calls emotional modelling.

“I can tell a robot that I’m feeling well, but I’m actually slumped over or holding my stomach, which doesn’t match what I’m saying,” she says. “We have to develop Pepper to not only recognize emotion, but to be able respond to it.” To do this, Pepper can make use of physical gestures, vocal intonations and changing the colour of the lights around its eyes.

A related area of study is persuasion, which is the focus of Nejat’s student Shane Saunderson (MIE PhD candidate). “Imagine if we had a robot with an emotional model and a persuasion strategy,” says Nejat. “Such robots would hopefully be able to persuade people to take their medication and do the exercises they need for rehabilitation.”

Over the years, Nejat’s lab has developed emotional models for several socially-assistive robots – Brian, Casper, Leia and Tangy – which are aimed at cognitively stimulating and promoting social interaction in long-term care. Xinyi Zhang (MIE MASc candidate) is working on implementing that model in Pepper and expanding its capabilities and activities.

Nejat plans to begin user studies in a hospital setting within a year. In the meantime, she is excited at the many possibilities Pepper, as well as artificial intelligence and robotics holds for the future of health care in Canada and the world.

“Our focus in the lab is improving the quality of life and promoting independence in healthy living,” says Nejat.“That’s why we are designing these robots.”