A team of U of T Engineering students is using the power of UV light to help stop the spread of COVID-19 and other virus-borne diseases.

They have prototyped a modular, smart UV lamp — dubbed LumineSense — that can be used to disinfect contaminated surfaces. By using sensors to monitor and adjust its light emission patterns, the device is designed to be more efficient than existing options, and at a lower cost.

The team is led by three graduate students: Michael Tisi (ECE MASc candidate), Jonathan Qu (MASc 2T0) and Ian Bennett (ECE PhD candidate). In the past year, over a half-dozen students have pitched in, including Christopher Alexiev (Year 3 EngSci), Alec Xu (Year 3 EngSci), Bipasha Goyal (Year 3 EngSci), Jordan Hong (Year 3 EngSci), Junho Jeong (ECE PhD candidate), Nima Bayat-Makou (ECE postdoctoral fellow) and Saila Maham Shama (EngSci 2T0).

The project received a boost from the Creative Destruction Lab (CDL) Recovery program, whose mission is to accelerate solutions to the COVID-19 crisis.

“The opportunity to apply technology to real-world problems is why many students were drawn to engineering in the first place,” says supervisor Professor Joyce Poon (ECE). “We wanted to make a positive difference with the great minds here at U of T Engineering.”

In the midst of the first lockdown in spring 2020, Poon sent out an open call to ECE students. Tisi was in the first group that signed up. He remembers the brainstorming meetings where they honed in on a problem to solve.

“Our original idea was to reduce the time it takes to disinfect transit vehicles after a shift and improve the turnaround,” says Tisi. “A lot of people were still using transit every day, especially front-line workers.”

The standard procedures typically involve liquid disinfectants, which are cheap, easy to use and widely available. However, disinfectants require personnel on site to spray and wipe, and hard-to-get-at areas can be easily missed. Chemicals in liquid disinfectants can also leave a residue on surfaces, and when used in environments such as dentist’s or doctor’s offices, can even harm sensitive equipment.

The team broadened its research and learned about another method often used in operating theatres and other such spaces: ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI). This system uses robots fitted with UV bulbs to sweep and spray the light indiscriminately on all surfaces, killing bacteria and viruses. The technique is effective, but these units are expensive, in the thousands of dollars.

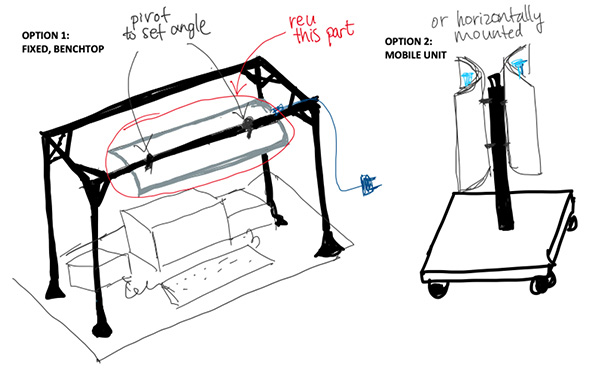

An idea took shape: to design a smaller, less costly UV lamp that could be mounted on various fixtures and employed in different environments, such as stores, restaurants, labs and medical offices.

But the main differentiator for LumineSense would be the incorporation of the latest sensor technology to monitor how the light is applied.

“On the edges of the reflective collimator, the part that houses the UV bulbs, we mounted sensors to measure the distance from lamp to surface,” says Tisi. “They calibrate the exact dosage and duration of UV light required for sterilization, then shut the lamp off.”

Most of the planning for LumineSense was done in virtual meetings, with students coordinating from different engineering departments and across different time zones. Some members worked out of the Max Planck Institute in Halle, Germany, where Poon serves as a Director.

The hands-on process of putting together the prototype had its share of challenges.

“To comply with social distancing rules, we were allowed three people in the lab,” says Tisi. “Sometimes the person who knew the precise details of the programming or the electronics wasn’t there that day.”

As COVID-19 extended into the new school year, team members were jumping aboard as others bowed out. This sometimes left knowledge gaps, but it also led to a new sense of resiliency.

“We’ve done a lot of self-teaching,” says Tisi. “I don’t have a background in electronics but I had to learn how a circuit board works. I had no microbiology background either. Now? Maybe just a little.”

The team will continue to work with CDL on the marketing and business angles for LumineSense. Because the lamp shows promise for applications beyond COVID-19, the most pressing issue is continued testing, specifically at a Contaminant Level 3 facility, where malicious viruses are secured for research.

“I’m proud of how our cohort of students has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic,” says ECE Chair Professor Deepa Kundur. “Not only have they adapted to constantly evolving conditions while keeping up their studies, they have actively engaged as problem-solvers to address a great societal need.”

Professor Ali Dolatabadi has recently joined the Department of Mechanical & Industrial Engineering (MIE). Prior to joining U of T Engineering, he was a Tier 1 Concordia University Research Chair in Multiphase Flow and Thermal Spray at Concordia University. His research focuses on how multiphase flows develops fundamental understanding of sprays for thermal spray processes, and of droplet dynamics, heat transfer and phase change for development and characterization of novel functional coatings.

Why did you choose MIE at U of T?

One of the main reasons I chose to join MIE is that I am a graduate from the department’s PhD programs, I was one of the first Centre for Advanced Coating Technologies (CACT) alumni. From my own experience, I know MIE is one of the best engineering departments in the world and is well-recognized both within North America and internationally.

U of T is also known as a hub for multidisciplinary research and for the highly qualified personnel that attend and work at the university. My research allows for a high degree of collaboration and I am looking forward to working with so many exceptional people within the Faculty and beyond.

Can you share a little about your research and what you like about it?

My research originally focused on computational and experimental analysis of multiscale multiphase flows and development of novel functional coatings via thermal spray processes. Thermal spray is a leading surface engineering technology due to its ability to produce coatings from tens of microns to millimetres in a large range of materials at moderate cost. Functional coatings are extensively used in various industries such as aerospace, automotive, and power generation to provide protective coatings on components that are exposed to heat, corrosion, erosion, and wear, etc. Coating developments involve thermofluids, materials science and chemistry – this is why multidisciplinary research plays a key role in my day-to-day activities.

What do you hope to accomplish, as an educator and as a researcher, over the next few years?

I’ve always found my role as educator one of the most satisfying parts of my job. I feel most successful when I can positively influence my students. My biggest goal is to continually focus on the next generation of students and how we can do the best for them. While I can’t wait to return to in person teaching, I can also see the opportunities COVID-19 has given us to rethink how we are doing things. We can take these lessons and integrate them into our future teaching and learning capabilities to provide our students with the best learning experience possible.

As a researcher, my biggest goal is to add another dimension to surface engineering and additive manufacturing. There is such a wide range of applications to the research I do and I’m looking forward to collaborating with my colleagues within industrial engineering, materials, chemical engineering, and aerospace engineering. I also hope to continue to focus on developing more environmentally friendly coating processes and applications.

Tell us a fun fact about yourself.

I love horses – and I have participated in many show jumping competitions.

Do you have any favourite spots from your time at U of T?

I have many good memories of my time in Toronto and I’m looking forward to being back on campus. During my PhD you would often find me at the Second Cup on College Street. I also used to love going to restaurants on Baldwin Street with my colleagues for lunch.

A U of T Engineering vehicle — one with a flashy chrome finishes and high-tech roof-mounted scanners — is getting a lot of admiring looks as it rolls around Toronto.

Meet UrbanScanner, a mobile testing laboratory on wheels. Constructed and driven by researchers in the Transportation and Air Quality group led by Prof. Marianne Hatzopoulou, (CivMin), the vehicle takes detailed measurements of air pollution as it varies over space and time.

Hatzopoulou and her team, including research associate Dr. Arman Ganji and MASc candidate Keni Mallinen, have partnered with Scentroid, a Toronto-based company developing sensor-based systems for urban air pollution monitoring, to create UrbanScanner.

The vehicle includes a 360-degree visual camera, a lidar (light detection and ranging) system, a GPS transponder, and an ultrasonic anemometer, as well as sensors for temperature, relative humidity, particulate matter and certain gas-phase pollutants.

A platform on the roof of the vehicle streams data to a cloud server, with air pollution measured every second and paired with the camera and lidar images. The ability to collect detailed location information enables air pollution data to be overlaid on city maps.

UrbanScanner can compare its real-time measurements of air pollution with features of a particular street or neighbourhood, such as traffic flow, number and height of trees and local building forms. It can also reveal patterns over time, whether it’s the daily rush hour or seasonal variations.

“Since September 2020, UrbanScanner has been collecting air quality data across Toronto, both along major roads and within Toronto neighbourhoods,” says Hatzopoulou.

Over the course of a single month UrbanScanner can log more than 2,280 km of driving, or more than 100 hours of data collection. That adds up to over 250,000 data points.

“This massive database will continue to grow as UrbanScanner collects data across seasons and will help us predict air quality in space and time, providing crucial information about population exposures in the city,” says Hatzopoulou.

Motorists preparing to turn at an intersection must quickly process several pieces of information before making their move: traffic signals, traffic signs, pedestrians, cyclists and, of course, other vehicles.

But if drivers become overloaded with information, the results can be deadly – and it’s often pedestrians and cyclists who pay the price.

Canadian and international studies show that driver inattention is a leading cause for collisions with pedestrians and cyclists – including those who were later identified as having right of way.

“It’s apparent that at certain intersections, we’re hitting the limits of drivers’ information-processing abilities,” says Professor Birsen Donmez (MIE).

“It’s apparent that at certain intersections, we’re hitting the limits of drivers’ information-processing abilities,” says Professor Birsen Donmez (MIE).

“There are so many things one has to pay attention to – and drivers are failing to do so given the issues we’re seeing with pedestrian and cyclist crashes.”

Donmez, who holds a Canada Research Chair in Human Factors and Transportation, leads an interdisciplinary research team that is collaborating with the City of Guelph to evaluate driver attention and gaze towards pedestrians and cyclists at intersections. The experiment will use eye-tracking equipment and cameras to better understand the interplay between driver attention, infrastructure design and collisions.

Funded by $25,000 from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada’s (SSHRC) Partnership Engage Grants program, the study will see Donmez team up with Professor Jay Pratt of the department of psychology in the Faculty of Arts & Science, Associate Professor Paul Hessof the department of geography and planning in the Faculty of Arts & Science and Liraz Fridman, transportation safety specialist with the City of Guelph and adjunct MIE professor.

“Addressing society’s biggest challenges often requires researchers to work across disciplines and, importantly, in partnership with stakeholders beyond academia,” says Professor Markus Bussmann, Chair of MIE.

“Professor Donmez’s study on road safety – an issue of importance to each one of us – exemplifies the approach by combining innovative use of technology with interdisciplinary scholarship and collaboration with a municipal partner.”

It’s one of six U of T-led initiatives to receive one-year Partnership Engage Grants, which are awarded quarterly to help researchers conduct timely and short-term research with a partner organization from the public, private or not-for-profit sectors. Four of the U of T projects received funding via the Partnership Engage Grants COVID-19 Special Initiative, which aims to support social sciences and humanities research on the impacts of the pandemic.

“I look forward to the outcome of this important project – and indeed all of the U of T-led projects that have received support from the SSHRC’s Partnership Engage Grants program,” says University Professor Ted Sargent (ECE), U of T’s vice-president, research and innovation, and strategic initiatives.

Over the past few years, Donmez and her team at the Human Factors and Applied Statistics Lab have been studying driver attention using tools such as driving simulators and eye-tracking wearables that examine where drivers look – and don’t look – when on the road. Their projects include a 2018 study, run in Toronto, in which eye-tracking equipment and cameras were used to assess where drivers allotted their visual attentions on the road.

However, the SSHRC-funded study is the first to involve a municipal partner.

“The City of Guelph has evidence on traffic conflict data – which is high-level data – but they want to understand the issue from driver behaviour and attention perspectives,” Donmez says.

For the Guelph study, around 50 participants will drive a pre-assigned route while wearing an eye-tracking camera in a vehicle fitted with cameras capturing internal and external scenes. Participants will drive for around 30 to 40 minutes each, with a break in between to prevent fatigue.

“We have a camera that faces the driver, which gives us information about their body position, head movement, emotional reactions and so on, and we have a road-facing camera which gives us a dashboard view to see objectively what the scene is in front of the vehicle as the person drives,” says Joelle Girgis (MIE MASc candidate), a graduate student in Donmez’s lab who will be leading the data collection and analysis. “The most critical equipment would be the eye-tracking glasses. These glasses will give us a view of what the driver is looking at even as they move their heads.

“We have a camera that faces the driver, which gives us information about their body position, head movement, emotional reactions and so on, and we have a road-facing camera which gives us a dashboard view to see objectively what the scene is in front of the vehicle as the person drives,” says Joelle Girgis (MIE MASc candidate), a graduate student in Donmez’s lab who will be leading the data collection and analysis. “The most critical equipment would be the eye-tracking glasses. These glasses will give us a view of what the driver is looking at even as they move their heads.

“This way, we know both what the objective road scene is in front of them, as well as where they’re gazing specifically.”

Once the data is collected, drivers’ turns at intersections will be coded according to whether they gazed at areas that were previously identified as being important.

“The question we’re asking is: Did they or did they not look at certain critical areas where a pedestrian or cyclist may appear?” says Girgis, whose master’s thesis will focus on the study. “So, we’ll view the videos and decide on whether the driver did or did not pay attention or directly gaze at a pre-determined area of importance.

“That gives us information that we can then turn into trends and statistics to see gaps. For example, drivers might not be checking their blind spot or right mirror when they’re stopped at a red light and need to turn right; maybe they’re overwhelmed; maybe there’s a lot of traffic coming from the left side; they’re also trying not to hit a pedestrian in front of them.

“So, there are all these things related to cognitive load that we might be able to infer based on the specific circumstance of where they are – and are not – looking.”

Girgis says driving routes and intersections will be chosen based on data about problem areas, as well as to cover different kinds of infrastructure and turn situations.

“There are certain intersections in Guelph that have a very high percentage of injury collisions, meaning that if a pedestrian or cyclist does get struck, the chances of them getting injured seriously or fatally are very high,” says Girgis, citing one particular Guelph intersection in which 100 per cent of vehicle-cyclist collisions reported between 2015 and 2019 resulted in the cyclist being killed.

“These are priority intersections where we’d like to understand what it is that’s causing the severity of collisions between vehicles and vulnerable road users.”

Girgis says the goal is to complete the driver data collection between April and September while respecting COVID-19 public health guidelines.

Donmez notes that driving data collected by the researchers still represents a “best-case scenario” since it won’t be able to take into account common in-car distractions such as cell phones and conversations with passengers.

“The participants aren’t doing anything else. They’re just focusing on their driving. Although it is an unfamiliar vehicle – so there’s that caveat there – I would expect that they have a lot less failures in our study compared to how they normally drive,” she says, adding that future studies may drill down on particular problem areas with the ultimate goal of informing policy and infrastructure design.

What might future solutions look like? Donmez says they generally come down to creating separation between drivers and vulnerable road users – both physically and in time.

“If you have barriers, you separate traffic,” Donmez says referring to the physical aspect. “But at intersections, the three modes of transportation will still merge. One of the issues is that cars can move at the same time as cyclists and pedestrians, so they’re not separated. In these cases, signals could be used to control traffic and decrease chances of conflict – that’s separation in time.”

She says her research shouldn’t be interpreted as blaming drivers. Rather, its focus is on finding ways to reduce the number of things competing for drivers’ attention – with the result being a safer environment for everyone.

“I walk everywhere in Toronto – or I used to a lot anyway, pre-pandemic – and over the years I’ve been starting to feel unsafe at certain intersections,” Donmez says, noting that Pratt, her research colleague, is an avid cyclist.

“I think we all have a stake in this as users of roadways and we all have a passion for this topic.”

With COVID-19 making it vital for people to keep their distance from one another, the city of Toronto undertook the largest one-year expansion of its cycling network in 2020, adding about 25 kilometres of temporary bikeways.

Yet, the benefits of helping people get around on two wheels go far beyond facilitating physical distancing, according to a recent study by three University of Toronto researchers that was published in the journal Transport Findings.

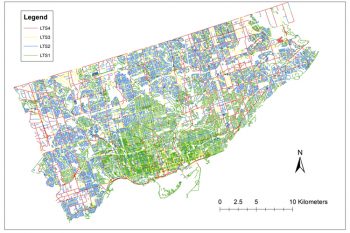

PhD candidate Bo Lin (MIE), as well as professors Shoshanna Saxe (CivMin) and Timothy Chan (MIE) used city and survey data to map Toronto’s entire cycling network – including the new routes – and found that additional bike infrastructure increased low-stress road access to jobs and food stores by between 10 and 20 per cent, while boosting access to parks by an average of 6.3 per cent.

“What surprised me the most was how big an impact we found from what was just built last summer,” says Saxe, an assistant professor in the department of civil and mineral engineering.

“We found sometimes increases in access to 100,000 jobs or a 20 per cent increase. That’s massive.”

The impact of bikeways added during COVID-19 were greatest in areas of the city where the new lanes were grafted onto an existing cycling network near a large concentration of stores and jobs, such as the downtown core. Although there were new routes installed to the north and east of the city, “these areas remain early on the S-Curve of accessibility given the limited links with pre-existing cycling infrastructure,” the study says.

In these areas, the new infrastructure can be the beginning of a future network as each new lane multiplies the impact of ones already built, Saxe says.

As for the study’s findings about increasing access to jobs, Saxe says they are not only a measure of access to employment but also a proxy for places you would want to travel to: restaurants, movie theatres, music venues and so on.

The researchers used information from Open Data Toronto and the Transportation Tomorrow 2016 survey, among other sources. Where there were discrepancies, Lin, a PhD student and the study’s lead author, gathered the data himself by navigating the city’s streets (as a bonus, it helped him get to know Toronto after moving here from Waterloo, Ont.).

“There were some days I did nothing but go around the city using Google Maps,” he says.

For Lin, the research has opened up new avenues of investigation into cycling networks, including how bottlenecks can have a ripple effect through the system.

The study, like some of Saxe’s past work on cycling routes, makes a distinction between low- and high-stress bikeways to get a more accurate reading of how they affect access to opportunities. At the lowest end of the scale are roads where a child could cycle safely; on the other end are busy thoroughfares for “strong and fearless cyclists” – Avenue Road north of Bloor Street, for example.

“It’s legal to cycle on most roads, but too many roads feel very uncomfortable to bike on,” Saxe says.

For Saxe, the impact of the new cycling routes shows how a little bike infrastructure can go a long way.

“Think about how long it would have taken us to build 20 kilometres of a metro project – and we need to do these big, long projects – but we also have to do short-term, fast, effective things.”

Chan, a professor of industrial engineering in the department of mechanical and industrial engineering, says the tools they used to measure the impact of the new bikeways in Toronto will be useful in evaluating future expansions of the network, as well as those found in other cities.

“You hear lots of debates about bike lanes that are based on anecdotal evidence,” he says. “But here we have a quantitative framework that we can use to rigorously evaluate and compare different cycling infrastructure projects.

“What gets me excited is that, using these tools, we can generate insights that can influence decision-making.”

The U of T team’s research, which was supported by funding from the City of Toronto, may come in handy sooner rather than later. Toronto’s city council is slated to review the COVID-19 cycling infrastructure this year.