U of T Engineering researchers are collaborating with Toronto startup FlowMix to study technology that could improve hot water distribution — eliminating cold showers and accidental scalding for the 1.9 million Canadians who live in condominiums.

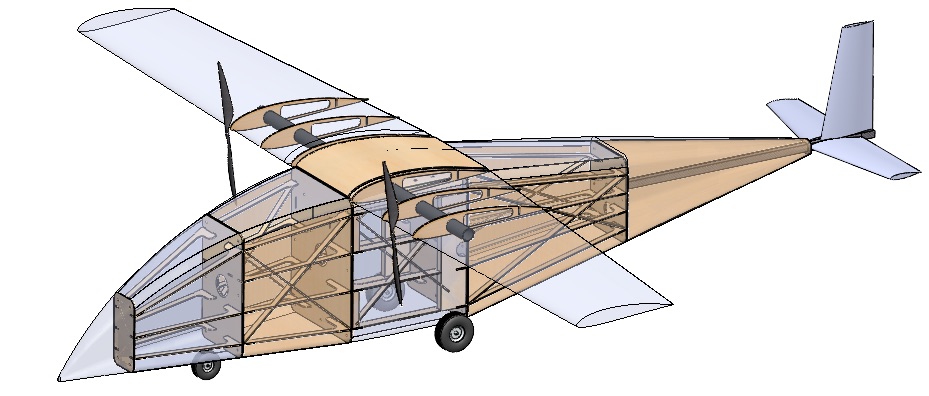

“The problem of hot water delivery in condos or high-rise buildings can be substantial. Not much has changed since mechanical valves — driven by pressure and temperature difference — were introduced over a century ago,” says Professor Pierre Sullivan (MIE), director of the Turbulence Research lab at U of T Engineering. Sullivan combines experimental and computational tools to better understand fluid physics with his research. His work has spanned aerodynamic control, wind power, small aircraft and weather gauges.

“The problem of hot water delivery in condos or high-rise buildings can be substantial. Not much has changed since mechanical valves — driven by pressure and temperature difference — were introduced over a century ago,” says Professor Pierre Sullivan (MIE), director of the Turbulence Research lab at U of T Engineering. Sullivan combines experimental and computational tools to better understand fluid physics with his research. His work has spanned aerodynamic control, wind power, small aircraft and weather gauges.

In residential buildings, where hot water must be supplied to multiple residents, there are demand spikes, such in the morning when people are getting ready for work. Longer periods of time when water is not in use, like overnight or while residents are at work, can also cause issues. During these down times hot water lines cool, which can lead to a chilly morning shower.

FlowMix, a company that designs hot water control systems, has developed a method that maintains a cycle of hot water in residential water delivery systems. Sullivan and his team reviewed the FlowMix design, and through testing and modelling, showed the effectiveness of the company’s solution.

“Simulations helped us to understand the flow structure inside the device for the purpose of improving the performance. We also modeled the traditional mixing devices to compare the performance of these devices with FlowMix,” said Ali Rahmatmand, a former post-doctoral fellow in the Turbulence Research lab.

“We also provided an AI model to predict the supply temperature of a building based on a basic demand and cold-water temperature to improve the control system,” said former post-doctoral fellow Marin Vratonjic.

With the team’s recommendations, FlowMix was able to optimize their system in both new construction and retrofitting high-rise buildings. This collaboration also means FlowMix can now quantify its impact on energy savings and CO2 emission reduction, which could help inform decisions made by condominium boards.

“The collaboration with Professor Sullivan and his team at the University of Toronto has been phenomenal. Quantifying and validating our best-of-class product was not a simple task,” says Louie Mazzullo, owner of FlowMix. “The results on this two-year project have exceeded even our initial high expectations.”

FlowMix clients include leading developer, Tridel, engineering firms, MCW Consultants Ltd., M&E Engineering Ltd., and contractors, Stellar Mechanical Inc., Network Mechanical.

“With the potential to apply this novel technology to any urban centre around the world, this Toronto innovation is world-leading,” says Sullivan.

Daniel Deza (Year 1 EngSci) always knew he was going to have friends at U of T Engineering — starting with his older brothers Arnaud (Year 3 EngSci) and Gabriel (Year 4 EngSci).

What he didn’t anticipate is just how close the three of them were going to get this semester.

All three Deza brothers are currently living — and studying — together at their parents’ house in Hamilton, Ont. Their older sister Anna (EngSci 2T0) graduated last spring and is now pursuing a PhD at the University of California Berkeley, while younger brother Emmanuel is also living at home while attending high school.

“My siblings told me lots of stories about what first year would be like, but nothing prepared me for this,” says Daniel.

Like all U of T Engineering students this semester, Daniel and his brothers have had to adapt to a challenging and unusual Fall term. In doing so, he and others have found new strategies to manage their studying and remote learning.

“Online learning is demanding and rather stressful, but having siblings in the same program is certainly a very fortunate situation to be in,” says Gabriel, who also mentors other first- and second-year students in Engineering Science online through the NSight Program.

“My brothers ask me about course content and course delivery, and we discuss funny stories about the teachers we have in common.”

Gabriel says he finds online learning easier than in-person classes, as they provide more flexibility in terms of when to watch the pre-recorded lectures. But Arnaud takes a different view.

“Compared to other semesters I feel very tired after a full day of Zoom lectures at my desk staring at my laptop screen for long periods of time,” he says. “One way to cope is to go on walks almost every day, either alone or with my family. I think this is essential even on the busy days, just to clear my mind and get some fresh air.”

First-year student Michael Simunec (TrackOne) developed his own strategy for online learning via a meeting early in the semester with U of T Engineering Learning Strategist Shahad Abdulnour.

“We produced a new schedule for managing time, work and classes that suit my learning style,” he says. “Though I only met with her once, the strategy we laid out has been extremely helpful for me.”

Simunec grew up in Toronto, but has lived abroad in Rome, Italy for the past eight years. He says he chose to live in residence at Trinity College in part because it made his university experience feel more real.

“It’s tough when you can’t see your classmates, and or talk to them after class as you normally would,” he says. “Still, there are a few people around on campus. We still have to stay distant and wear masks in common areas, but the fact that I’m around other people in a similar position, including a few people in engineering, has helped.”

Outside of class, Simunec is doing what he can to get involved in co-curricular activities. When public health regulations allowed, he was able to join in pick-up games of soccer, wearing a mask of course. He is also looking into joining the U of T Chapter of Engineers Without Borders.

“I think they’ve done a good job with the transition to online,” he says. “All the information you need is available and there are people who can answer your questions. I’m hoping to get more involved as I move into upper years.”

Engineers Without Borders is not the only student club that is keeping its activities going this year. Samuel Looper (Year 4 EngSci) is the Executive Director of the University of Toronto Aerospace Team, and says the team is running its full slate of design projects as best as it can under the circumstances.

“We already had good systems for remote design collaboration,” he says. “We use Google Drive for file sharing, Slack for messaging, and other tools for task tracking, meetings and socials. There are some timeline complications due to the lack of in-person manufacturing, but most of the early stages can be done online.”

Looper says UTAT has also been able to keep up its outreach and professional development activities, including the Women of Aerospace speaker series and various STEM education events in partnership with Hi-Skule and other community organizations

“We’ve definitely had challenges this semester, particularly engaging with new students,” says Looper. “Nonetheless, we are on track to retain a record number of students into next semester, which points to the fact that there is definitely still a need for extracurriculars and student community events.”

Amelie Wang (Year 2 ECE) is studying from Shantou, in China’s Guangdong region. She says that being in a time zone that is 12 hours ahead of Toronto’s hasn’t affected her as much as one might think.

“Some of my friends still follow Toronto’s time zone, but I really can’t do that as sleeping is so important for me,” she says. “With the international timetable, the classes are mostly in the daytime, and all courses are recorded, so I can always watch the recordings if I do not want to stay up late or wake up early.”

Wang says that precisely because of this flexibility, online learning requires more self-control than in-person.

“It was really hard for me to follow the schedule in the beginning, but gradually I got used to it,” she says. “The key was to keep track of every day’s tasks and avoid procrastination.”

Outside of classes, Wang is continuing to volunteer as an ECE ambassador, including participating as a student panelist and answering live questions from prospective students as part of U of T Engineering’s Fall Campus Day recruitment event. She is circumspect about the impact of this semester on her overall degree program.

“As a second-year student, the pandemic hasn’t affected my journey much so far,” she says. “What I am focused on right now is getting a good internship for the coming summer, hopefully one where I can actually work with people in person.”

It’s not just undergraduate students who have been dealing with an unprecedented semester. Julien Couture-Senécal (EngSci 2T0, BME PhD candidate) started his doctoral program in September.

Although labs are open, booking time in them can be difficult due to careful restrictions on how many people are allowed to be in them at any given time. Instead, Couture-Senécal says he’s been using the extra time to complete course requirements and enhance his skills in coding and statistical experimental design.

He has also been attending a lot of online seminars offered by U of T and other institutions, such as the Medicine By Design Global Speaker Series or the Harvard University Bioengineering Seminar Series.

“You don’t get free pizza or sandwiches as you might on campus, but they still quench my thirst for knowledge,” he says.

Couture-Senécal says that hardest change has been the lack of human interaction.

“Research shows that graduate students are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression, so connecting with my peers remotely has been helpful to keep the stress levels low,” he says.

“My lab has organised weekly virtual coffee chats to take a breather and catch up. I took the down-time as an opportunity to reflect on my unhealthy pre-pandemic habits. I’ve also been learning about how to close the stress loop and discovering that I am more of an emotional being than I realized.”

Despite the challenges, Couture-Senécal still sees plenty of opportunities, and is optimistic that he can still make the most of this academic year.

“I am a firm believer that this moment of reflection will help change the graduate school experience for the better,” he says.

Professor Vaughn Betz (ECE) has been elected a Fellow of the U.S. National Academy of Inventors.

The Academy honours academic inventors who have demonstrated “innovation in creating or facilitating outstanding inventions that have made a tangible impact on the quality of life, economic development, and the welfare of society.”

Betz has pioneered new approaches to evaluating and optimizing Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) architectures. FPGAs are computer chips that can be reprogrammed after manufacturing to allow for agile, reconfigurable hardware systems. They are used in a wide variety of applications, such as wireless communications, ultrasound imaging machines, automotive electronics and video broadcast.

Betz created a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) flow and methodology, known as Versatile Place and Route (VPR), which is now the world’s most commonly used toolset for modelling new FPGA ideas. He co-founded Right Track CAD with Professor Jonathan Rose (ECE) to commercialize his research in 1998, and helped grow the company to 10 engineers and several million dollars in yearly revenue.

In 2000, Right Track CAD was acquired by one of its customers, Altera Corporation (now part of Intel). Betz held several leadership positions within Altera over the next 11 years, ultimately as Senior Director of Software Engineering. He is the architect of many features within Altera’s Quartus CAD system, including the placement and routing engine and the power optimization tools, which are used daily by tens of thousands of design engineers worldwide. He is also one of the architects of the first five generations of the Stratix and Cyclone FPGA families, which have cumulative sales of over $15 billion U.S. to date.

Betz is the NSERC/Intel Industrial Research Chair in Programmable Silicon and a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). He has received 13 best or most significant paper awards from leading conferences, as well as the Ontario Professional Engineers Medal for Engineering Excellence. Betz has published over 120 technical articles, one book and four book chapters on programmable logic and CAD. He holds 100 U.S. patents.

“As an engineer, inventor and entrepreneur, Professor Betz reflects the standard of excellence for which U of T Engineering is known,” says Chris Yip, Dean of U of T Engineering. “His work has had an exceptional impact on the adoption and commercialization of FPGA technology, and on academic research worldwide. On behalf of the Faculty, my warmest congratulations to him on this richly deserved honour.”

U of T Engineering students Mahia Anhara (Year 3 CivE), Alaa Itani (CivMin PhD candidate), and Felita Ong (CivMin MASc candidate) have been awarded scholarships by the Women’s Transportation Seminar (WTS) Toronto area chapter. Joanna Ilunga-Kapinga, who is pursuing a master’s in Planning at U of T, was also recipient. The scholarships support outstanding female students in the transportation sector.

WTS International was established in 1977 to provide women with professional development, encouragement and recognition, to support their advancement in transportation professions. It is a member organization with chapters worldwide, including the WTS Toronto Area Chapter established in 2013. The scholarships were announced at the WTS Virtual Conference on Wednesday, Dec. 3, 2020.

After completing her third year, Anhara began working as an engineering intern in the Vision Zero Projects Unit at the City of Toronto, as part of her Professional Experience Year Co-op (PEY Co-op). Currently in this role, she is helping to eliminate traffic-related fatalities and serious injuries by designing safer streets and intersections for all road users. She was also involved in designing temporary bike lanes on a major road in her neighbourhood, which enables her to bike conveniently and safely to stores, the library, and parks.

After completing her third year, Anhara began working as an engineering intern in the Vision Zero Projects Unit at the City of Toronto, as part of her Professional Experience Year Co-op (PEY Co-op). Currently in this role, she is helping to eliminate traffic-related fatalities and serious injuries by designing safer streets and intersections for all road users. She was also involved in designing temporary bike lanes on a major road in her neighbourhood, which enables her to bike conveniently and safely to stores, the library, and parks.

At U of T, Anhara is very involved in U of T Engineering clubs. She is currently the PEY Co-op Representative and a mentor in the Civil Engineering Discipline Club. She is also a Project Manager in the Canadian Electrical Contractors Association (CECA) – U of T Student Chapter.

Mahia believes that roads should not only be designed for motorists, but for all road users, such as pedestrians, cyclists and transit users so that everyone can access amenities and opportunities safely and equitably.

“Many North American cities have been designed in a way to prioritize automobiles,” she says. “This has led to the rise of inequality, degradation of physical and mental health, and the exacerbation of climate change. I’m inspired to study transportation to help address these issues and make cities more walkable, bikeable, and transit-friendly.”

She wants to pursue a career in developing transportation systems that provide people from all walks of life with improved transit access and safer streets for biking and walking. She looks forward to being an agent in transforming cities to become more resilient and vibrant.

Itani specializes in public transit operations and research under the supervision of Professor Amer Shalaby (CivMin). She is interested in the field of bus-hailing, dial-a-ride, and flexible transit services where her research focuses on planning and understanding the policies and guidelines of these services in this era of emerging technology and automation.

An active volunteer, Itani is currently the administrative officer of the University of Toronto Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Student Chapter. She also participated in multiple volunteer roles at the recent TransitData 2020 online international symposium.

Since January 2020, Itani has presented her research at four public forums, beginning with the prestigious Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board in January. In April, she presented at Esri Canada’s GIS in Education and Research Conference. In June, Itani presented at both Transformative Transportation ’20 and the iCity Research Days Webinar Series.

In addition to volunteering and presenting her research, Alaa also participated in a hackathon on urban transit data, and most recently, in the 2020 ITS Canada Essay Competition where she won second prize.

Alaa is motivated by her personal, lived experience: “I have a passion for transit and I will continue working towards more equitable transportation options, as I grew up in a city that did not have a public transport network, and I struggled a lot getting around in my own city.”

Ong has experience in transportation planning and operations through her work in both the public and private sectors. Her research focuses on investigating the demand competition between ride-hailing services and public transit to help transit agencies make evidence-based policies and planning decisions.

Ong has experience in transportation planning and operations through her work in both the public and private sectors. Her research focuses on investigating the demand competition between ride-hailing services and public transit to help transit agencies make evidence-based policies and planning decisions.

She is passionate about introducing young students to science, technology, engineering and math (STEM), including transportation engineering. She is currently a high school mentor through the Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) U of T Chapter, and was previously an instructor for the UBC Geering Up Engineering Outreach, a non-profit organization that promotes STEM to young students throughout British Columbia.

Ong is proud that her research has real-world benefits: “Transportation is a multidisciplinary field that has a direct impact on everyday lives. I hope to contribute to a sustainable, equitable, and efficient transportation system.”

After nearly a year of studying COVID-19, scientists are still grappling with fundamental questions — including understanding the dominant modes of transmission and predicting how “superspreading” events arise. A newly improved model produced by engineers and physicists could help.

Last summer, Professor Swetaprovo Chaudhuri (UTIAS) and his colleagues developed what they called a “first-principles modelling approach” to understanding the factors that impact COVID-19 spread.

The team — which also included Professor Abhishek Saha at the University of California San Diego, and Professor Saptarshi Basu of the Indian Institute of Science — outlined their findings in a paper published in the journal Physics of Fluids.

Unlike epidemiological models that predict the spread of a disease based on empirical data from past outbreaks or from estimating person-to-person contact, this model makes use of fundamental flow physics concepts, droplet and jet aerodynamics, evaporation and related thermodynamics.

The idea was to simulate the physical path of droplets expelled by infected people, along with their physical state. The model can be used to predict the probability of transmitting the infection from one person to another

“In the previous paper, we analysed lifetime and travel distance of individual respiratory droplets of different sizes,” says Chaudhuri. However, one respiratory event produces not one droplet but a jet: a cloud with a large range of droplet numbers and sizes. When these droplets evaporate, they leave behind solid nuclei, which also form part of the cloud.

Led by Professor Chaudhuri, the team published their improved model in another paper in Physics of Fluids, which takes account of this cloud-like aspect. The model draws inspiration from the experimental works of Professor Lydia Bourouiba at MIT, whose team has published extensively on the fluid dynamics of disease transmission.

The team also accounted for interactions between people and the cloud in a social setting, which was modelled using equations originally designed to describe collisions between molecules in a chemical reaction.

Distinctions can be made between different types of respiratory events — coughing, breathing, singing, sneezing or even talking. The model also incorporates the most recent information about typical SARS-CoV-2 viral load and virus lifetimes.

Combining the “physics of the cloud” with the “physics of the crowd” enables the model to produce estimates of the basic reproduction number, R0, under various scenarios, as well as how superspreading events can occur.

R0 can be thought of as the expected number of new cases that each current case will give rise to over its lifetime: if it is above one, the disease will continue to spread exponentially; if not, the pandemic will eventually burn out.

As before, the team tested their basic droplet model with an acoustic levitator, a device that uses sound waves to cause droplets of saline solution to float suspended in air. This time, the team used real saliva of “a healthy subject who was Covid-19 negative.” The experiment was performed at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore and results will be published in a future paper.

Inferences of the model include:

- The most lethal droplets from a cough were those with initial sizes of 10 to 50 microns. This is a size blocked by most masks, however Chaudhuri points out that by the time they are inhaled, these droplets could shrink to less than 20% of their original size.

- Droplets — and especially the dried-out nuclei that contain the virus particles — can easily spread 12 feet or further. However, with distance, the droplet cloud expands and gets diluted, which reduces the probability of infection.

- Without ventilation, droplet nuclei are persistent, meaning they remain suspended in air for long periods of time. Because of this persistence, they have to potential to infect larger numbers of people than the initial droplets.

As for advice to reduce the spread, Chaudhuri says while he is not the expert, the following holds true from their model: wear a mask (three layered masks are most effective), avoid spending time indoors in public places, improve ventilation, keep as far apart as possible, and also wash hands frequently.

Chaudhuri acknowledges that this model is based on an idealized scenario and includes a number of assumptions. One of the most important relates to what degree the virus particles embedded inside the droplets remain infectious after the liquid surrounding them has evaporated, a question he says is “still an ongoing research problem for virologists.”

But he says the value of a physics-based approach is that the same basic framework can be adapted to different scenarios simply by adjusting certain parameters or the boundary conditions of the analysis.

“Additional complexities in terms of room size, partitions, ventilation, could be introduced and accounted for,” he says.

Going forward, the team hopes to collaborate with more researchers outside their discipline to address some of the areas where their model could be further improved. Chaudhuri stresses the multidisciplinary nature of the challenges posed by COVID-19.

“This is a problem which involves, doctors, public health researchers, epidemiologists, virologists, mathematicians, computer scientists, as well as experts in aerosols and fluid mechanics,” he says. “We have to work together to gain a complete picture.”

A team of researchers from U of T Engineering has created a new process for converting carbon dioxide (CO2) captured from smokestacks into commercially valuable products, such as fuels and plastics.

“Capturing carbon from flue gas is technically feasible, but energetically costly,” says Professor Ted Sargent (ECE), who serves as U of T’s Vice-President, Research and Innovation. “This high energy cost is not yet overcome by compelling market value embodied in the chemical product. Our method offers a path to upgraded products while significantly lowering the overall energy cost of combined capture and upgrade, making the process more economically attractive.”

One technique for capturing carbon from smokestacks — the only one that has been used at commercial-scale demonstration plants — is to use a liquid solution containing substances called amines. When flue gas is bubbled through these solutions, the CO2 within it combines with the amine molecules to make chemical species known as adducts.

Typically, the next step is to heat the adducts to temperatures above 150 C in order to release the CO2 gas and regenerate the amines. The released CO2 gas is then compressed so it can be stored. These two steps, heating and compression, account for up to 90% of the energy cost of carbon capture.

Geonhui Lee, a PhD candidate in Sargent’s lab, pursued a different path. Instead of heating the amine solution to regenerate CO2 gas, she is using electrochemistry to convert the carbon captured within it directly into more valuable products.

“What I learned in my research is that if you inject electrons into the adducts in solution, you can convert the captured carbon into carbon monoxide,” says Lee. “This product has many potential uses, and you also eliminate the cost of heating and compression.”

Compressed CO2 recovered from smokestacks has limited applications: it is usually injected underground for storage or to enhance oil recovery.

By contrast, carbon monoxide (CO) is one of the key feedstocks for the well-established Fischer-Tropsch process. This industrial technique is widely used to make fuels and commodity chemicals, including the precursors to many common plastics.

Lee developed a device known as an electrolyzer to carry out the electrochemical reaction. While she is not the first to design such a device for the recovery of carbon captured via amines, she says that previous systems had drawbacks in terms of both their products and overall efficiency.

“Previous electrolytic systems generated pure CO2, carbonate, or other carbon-based compounds which don’t have the same industrial potential as CO,” she says. “Another challenge is that they had low throughput, meaning that the rate of reaction was low.”

In the electrolyzer, the carbon-containing adduct has to diffuse to the surface of a metal electrode, where the reaction can take place. Lee’s experiments showed that, in her early studies, the chemical properties of the solution were hindering this diffusion, which in turn inhibited her target reaction.

Lee was able to overcome the problem by adding a common chemical, potassium chloride (KCl), to the solution. Though it doesn’t participate in the reaction, the presence of KCl greatly speeds up the rate of diffusion.

The result is that the current density — the rate at which electrons can be pumped into the electrolyzer and turned into CO — can be 10 times higher in Lee’s design than in previous systems. The system is described in a new paper published today in Nature Energy.

Lee’s system also demonstrated high faradaic efficiency, a term that refers to the proportion of injected electrons that end up in the desired product. At a current density of 50 milliamperes per square centimetre (mA/cm2), the faradaic efficiency was measured at 72%.

While both the current density and efficiency set new records for this type of system, there is still some distance to go before it can be applied on a commercial scale.