A multidisciplinary team is looking at the possibility of using the omnipresence of smartphones to monitor certain aspects of mental health.

By recording short bursts of ambient noise and mapping that audio over time, the team found that keeping a regular daily routine was negatively correlated with subjects self-reporting a symptom of depression.

The team is led by Daniel Di Matteo (ECE PhD candidate), and supervised by Professor Jonathan Rose (ECE) and psychiatrist Dr. Martin Katzman. Their new app turns on a smartphone’s mic for 15 seconds every 5 minutes. The team installed the app on the phones of 112 volunteer subjects to record ambient noise over a two-week period.

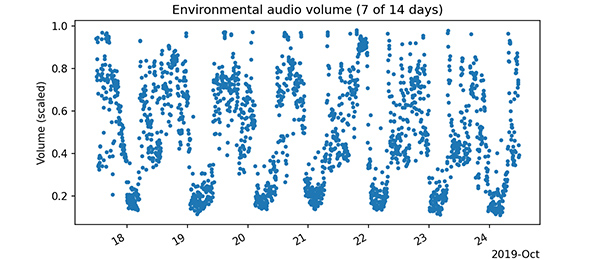

The team then extracted the average volume of noise for short, discrete durations. When plotted over time, this volume data has peaks and troughs like a wave whose regularity can be quantified. To achieve a measurement of regularity this way, by means of ambient noise, has not been done before.

“It’s well known — though not perfectly understood — that there’s a connection between mental health and regularity in your days,” says Di Matteo.

“This regularity measurement is a statistic, like blood pressure might be in a medical study,” he adds. “We looked for a relationship between this statistic and the subject’s mental health questionnaire scores.”

The findings of this explorative study, the first of three, were published in August 2020 in the medical and health research journal JMIR.

The driving force behind the research is to gather and objectively process passive, continuous data to compare alongside a broad range of symptoms from social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, depression and general impairment.

“Consider how mental health monitoring currently works,” says Rose. “Patients visit their therapist every week or so by going to a clinic or office. The patient chooses how to present themselves and the therapist interprets what they hear.”

But with a smartphone in every backpack, pocket or purse these days, there’s an opportunity to gather data far more frequently. Because intermittent recording goes unnoticed, the data-gathering is passive, too: the act of measuring isn’t changing what’s being measured.

One of the challenges for an observational study like this — as with many similar studies in this field — is managing privacy protections.

The research ethics board set limitations on how the team could use the audio. They couldn’t listen to it, nor could they keep it for longer than a few weeks; any discernible words had to be stored in isolation so that the original conversation couldn’t be recreated.

It has long been known that the presence/absence of voices is associated with depression. A second study, currently in review, considers this word-based data, while a third will look at the predictive potential of a robust app that includes data for location, on/off screen activity and motion detection.

If it’s possible to build a medical model of mental health, based only on smartphone data, the innovation could be a valuable asset for the field.

“When someone’s going into depression they just kind of fade away,” says Rose. “Imagine an app with the capability to notify a spouse or a parent when this happens. Imagine one that could more finely track the efficacy of a prescription.”

His imagination — and research — has been fired up by such scenarios for seven years since the inception of The Centre for Automation in Medicine and his collaboration with Dr. Martin Katzman and fellow researchers at the S.T.A.R.T. Clinic.

“It’s a true partnership,” says Rose of his research partners in the clinic. “They learn what’s possible with machine learning while we learn aspects of psychiatry and statistics. We don’t just do what they tell us.”

He adds with a smile, “That goes both ways, of course.”

Professor William R. Cluett (ChemE) has been recognized by the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA) with a 2020 OCUFA Teaching Award. This award recognizes university faculty who have made exceptional contributions to postsecondary education through teaching and leadership.

Cluett is currently the Director of the Division of Engineering Science. He has held several academic leadership roles in the Faculty, including Vice-Dean, First Year and Vice-Dean, Undergraduate, among others. Cluett was Chair of the Division of Engineering Science from 2005 to 2011. In these roles, he led the development of programs that helped reshape the Faculty’s approach to engineering education.

As Vice-Dean, First Year, Cluett led the development and launch of the Da Vinci Engineering Enrichment Program (DEEP). DEEP has since expanded into a series of programs, which attract close to 1,000 high school students each summer. As Vice-Dean, Undergraduate, he played a key role in the creation and implementation of Engineering Strategies and Practice, the Faculty’s flagship first–year design and communication course.

And as Chair of the Division of Engineering Science, he led the development of a unique major in Engineering Mathematics, Statistics, and Finance. Cluett also oversaw a significant expansion of summer research opportunities for engineering science students, which contributed to the Division winning the University’s Northrop Frye Award for the Integration of Teaching and Research in 2012.

As an educator, Cluett has used innovative techniques in his classroom for decades, such as active learning and computer-based simulation. In 2009, he also created a new course for first–year engineering science students, Engineering Mathematics and Computation, which uniquely integrates theory and computation in a single course.

In 2014, Cluett received the Bill Burgess Teacher of the Year Award for Large Classes from the Department of Chemical Engineering & Applied Chemistry, in recognition of his outstanding instruction in his home department. In 2016, he received the Faculty’s Sustained Excellence in Teaching Award, recognizing a faculty member who has demonstrated excellence in teaching over the course of their career. In 2018, Cluett garnered the President’s Teaching Award, U of T’s highest honour for teaching. He is also a member of the University’s Teaching Academy.

“Over the past 25 years Professor Cluett has played a leading role in developing many of the programs that make U of T Engineering one of the world’s best engineering schools,” said Dean Chris Yip, U of T Engineering. “On behalf of the Faculty, my warmest congratulations to him on this well-deserved honour.”

2019-2020 OCUFA Teaching and Academic Librarianship Award Recipients from OCUFA on Vimeo.

Bipasha Goyal (Year 3 EngSci) is creating what she hopes will be the newest line of defence against the global COVID-19 pandemic: a smart UV lamp.

“Hospitals already use a similar method called ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) to sterilize operating theatres and other spaces,” says Goyal. “The challenge is that these systems are very expensive, and it’s hard to ensure a sufficient UV dosage has been applied to a surface.”

Goyal is part of Team LumineSence, which also includes her supervisor, Professor Joyce Poon (ECE), and several other U of T Engineering students. Together, they are designing a new UVGI system that would be more effective and less costly than currently available machines.

One of their insights is to focus on both the light emission and light sensing aspects of the device.

“Much of the innovation in existing systems has been the autonomous mobile robot supporting the lamps,” says Goyal. “But then it comes to the lamps themselves, the emission pattern is usually not shaped or purposefully directed. The lamps have not been integrated with any sensors to monitor their efficacy.”

Team LumineSense is creating an integrated system that would do both of these things, and could be mounted on mobile racks, or on static surfaces such as ceilings and table tops. The team and its flagship product sprung from CDL Recovery, a program from U of T’s Creative Destruction Lab that focuses on smart solutions to accelerate the world’s recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

Using smart sensors and carefully designed algorithms, the device would adapt its output to provide optimal UV light exposure to sterilize surfaces. The sensors would also enable it to automatically shut down if human presence is detected, minimizing the risk of exposure to harmful UV radiation.

Currently, Goyal’s contribution to the project is being supported by a Mitacs Research Training Award (RTA), which is matched 1:1 by U of T Engineering. She is among 87 U of T Engineering undergraduate and graduate students whose research projects have earned Mitacs RTAs, with topics ranging from data science and artificial intelligence to advanced materials and manufacturing.

Many of the projects also involve partner organizations. In Goyal’s case, it’s the Max Planck Institute (MPI) of Microstructure Physics in Germany, where Poon serves as Director. Early in the project, MPI researchers brought new ideas, advice and insight to LumineSense.

“Communicating with a large team across multiple time zones was a difficult task,” says Goyal. “It taught me the importance of being in regular communication and seamlessly distributing roles and responsibilities.”

“As engineers, we contribute to solutions to better the world,” says Poon. “I am very proud of Bipasha and all of the students and postdocs who have come together for this team project.”

In addition to enhancing her technical understanding of light sensing and autonomous robotics, Goyal says the project is also teaching her about the challenges of translating research from the lab to the marketplace.

“The overall features and use cases of the design required us to identify potential stakeholders, which include schools, research labs and even residential buildings, and create an adaptable modular design to better suit their needs” she says.

“COVID-19 affected everyone professionally and personally. I consider myself very lucky to have found this opportunity to be involved in such a meaningful project.”

Moneyball was just the beginning.

The 2011 film, based on a 2003 nonfiction book by Michael Lewis, introduced the world to the idea that, rather than obsessively trying to recruit and retain star players, baseball teams can improve their performance by analyzing and optimizing key statistics across their roster.

Nearly a decade later, Professor Timothy Chan believes the time is ripe to take the approach to a whole new level. With funding from a Connaught Global Challenge award, he aims to make U of T a world-leading hub in sports analytics.

“With the rise of advanced video tracking and wearable devices, sports teams have more data than ever before,” says Chan. “The challenge now is for them to interpret, analyze and make use of this data, to transform it into valuable insights.”

Chan is ideally positioned to lead the effort. The director of U of T Engineering’s Centre for Analytics and Artificial Intelligence Engineering (CARTE), he has extensive expertise in big data and optimization. He has published widely on their application to sports such as hockey and collaborated with the Canadian Olympic Committee.

He has even cracked a decades-old open question in baseball analytics, by borrowing classical ideas from industrial engineering – this work was awarded first place in the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in 2013.

But Chan emphasizes that in order for sports analytics to be effective, it can’t happen in isolation. His large and multidisciplinary team of collaborators includes physicians, kinesiologists, economists, mathematicians, management experts, and computer scientists.

“Everyone has a role to play,” he says.

While the Moneyball approach originally focused on team performance, Chan says there are many other important aspects of sports that can be enhanced through analytics. These include athlete fitness, safety and health, fan engagement, and even the management of fantasy sports or e-sports leagues.

The team has laid out a few “pathfinder projects” that will serve as proof of the concept. One example comes from the world of freestyle snowboarding, where devices known as Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) are used to record athlete data such as acceleration, rotation and heading.

“Our collaborators at the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific have collected IMU data from hundreds of sessions,” says Chan. “The first step will be to take that data and use it to compute metrics such as air time, jump height and take-off speed. Eventually, this should help us uncover the characteristics of successful tricks.”

The plan also includes symposiums and summer schools to help train the next generation of experts in sports analytics. The $250,000 Connaught Global Challenge award will help sustain the project over the next two years.

“My hope is that this award lays a solid foundation for team-building across campus, and sets the university up to be a world leader in this growing area,” says Chan.

“This project embodies the kind of innovative thinking for which our Faculty is known,” says Professor Ramin Farnood, Vice-Dean, Research at U of T Engineering. “Professor Chan has built up an impressive team of collaborators, from a wide range of disciplines, who are poised to make a tremendous, positive impact both here in Canada and around the world.”

aUToronto has placed first in an intercollegiate challenge to transform an electric car into a self-driving one — their third consecutive win.

“All of us take pride in the work that we have done at aUToronto,” says Jingxing “Joe” Qian (EngSci 1T8 + PEY, UTIAS MASc candidate), Team Lead for aUToronto. “The competition results clearly reflect the high calibre and dedication of the team.”

The team also took the top overall prize for the most cumulative points over the three years of the AutoDrive Challenge. Second place went to Texas A & M, with Virginia Tech scoring third. The other schools in the competition were: University of Waterloo, Michigan State, Michigan Tech, North Carolina A&T State, and Kettering University.

The AutoDrive Challenge began in 2017, when each of the student-led teams was provided with a brand-new electric vehicle, a Chevrolet Bolt. Their task was to convert it into an autonomous vehicle, meeting yearly milestones along the way.

Sponsors of the AutoDrive include General Motors, the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) and a number of other companies that produce hardware and software for self-driving cars.

The U of T team took the top spot at the first meet of the competition, held in the spring of 2018 at the General Motors Proving Grounds in Yuma, Ariz. In the second year, they again placed first at the competition, which took place in MCity, a simulated town for self-driving vehicle testing, built at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The third yearly meet was originally scheduled to take place last spring at the Transportation Research Center in East Liberty, Ohio. However, it was postponed and reorganized due to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

“The goal of this year’s challenge was to simulate an autonomous ride-sharing scenario,” says Qian. “That means the car needed to arrive at a sequence of pre-determined address points and perform pseudo pick-up and drop-off behaviours. The routes would have been much longer and more complex compared with Year 2.”

In the absence of a live event, the organizers used what are known as “static event” scores, which are based on reports and presentations that the teams could submit remotely. These included an analysis of the social responsibility aspects of the project, the overall conceptual design and the results of a number of sophisticated computer simulations.

Qian says that the latest iteration of Zeus includes a number of enhancements, including improvements in perception, path planning and GPS-free localization. To make them, the aUToronto team overcame numerous challenges, not the least of which was coordinating more than 50 team members who were working remotely on the project.

“We are located in many different places around the world, so team building and organization becomes extremely important,” says Qian. “We have weekly meetings online where sub-team leads present their updates to the rest of the team, and we have also been planning virtual paper talks and knowledge sharing sessions.”

“aUToronto has been focused on putting together a top-notch self driving car for three years now,” says Keenan Burnett (EngSci 1T6+PEY, UTIAS MASc candidate), who served as aUToronto’s Team Lead through the first two years of the AutoDrive Challenge. “This win is the result of hundreds of hours of work by our team.”

“As a faculty advisor, I have watched with awe as the 100%-student-run team really seized this unique opportunity,” says Professor Tim Barfoot (UTIAS). Barfoot, along with Professor Angela Schoellig (UTIAS) is one of the two co-Faculty Leads of the team. He also serves as Associate Director of the University of Toronto Robotics Institute and the Chair of the Robotics Option offered by the Division of Engineering Science.

“Robotics is a very hands-on discipline, so experiences such as the AutoDrive Challenge are needed to complement classroom learning,” says Barfoot “I am deeply grateful to SAE and GM for organizing this activity and the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering for their ongoing support through the Dean’s Strategic Fund. I feel our graduates are better prepared to head into the exciting field of autonomous vehicles than perhaps anywhere in the world at this moment in time. The fact that we won the competition is a bonus.”

The competition has been rolled into a fourth year, with a live meet set to take place sometime in 2021, again at MCity in Ann Arbour, Mich.

“We’re very proud the results of this third-year competition and looking forward to raising the bar yet again at the fourth-year competition,” says Burnett. “Although we’re disappointed we didn’t get to show off our autonomous functions this year, we’re looking forward to going back to MCity and demonstrating our Level 4 self-driving car.”

But aUToronto is also thinking beyond the end of the AutoDrive Challenge.

“We’ve always said we do not want to design a system that is specific towards this competition,” says Qian. “Our goal is to achieve full autonomy under many different scenarios.”

In celebration of alumna Elsie MacGill’s Heritage Minute, released today, U of T Engineering News has republished “The Rise of Elsie MacGill,” the cover story from the 2015 edition of Skulematters.

Like their colleagues in the United States, Canadian engineers had many reasons to be proud as the Society of Women Engineers (SWE) — a not-for-profit educational and service organization — marked its 60th anniversary celebration in 2010. The creation of SWE in 1950 inspired engineers internationally and touched careers and lives in many countries. Canadians have a unique reason to applaud the Society’s founders, however, because they gave a boost to one of Canada’s national heroines, a person who went on to change the country’s social, economic and legal fabric, and a person who continues to fascinate and inspire six decades later.

Elsie MacGill (ElecE 2T7) was involved in SWE early on, being named an honourary member in 1953. By that time, she had established herself as a leader in the engineering profession for many years. Still, despite her accomplishments, MacGill said that she was truly “astonished” when, that same year, the selection committee made her the unanimous choice to receive the second SWE Achievement Award and the mantle of outstanding woman engineer for that year. Her friends and admirers, however, were not astonished at all.

A succession of firsts

By this point in her life, MacGill had attracted an impressive collection of engineering awards and recognitions and had been celebrated as the rst woman aeronautical engineer. She had completed graduate studies in the eld; conducted research; worked as a professional and introduced new innovations, including the design of an entire aircraft in the 1920s and 1930s.

Her profile in the profession increased dramatically early in the Second World War when the 33-year-old MacGill was appointed chief aeronautical engineer at the booming Canadian Car and Foundry plant in Fort William, Ont. There, fighter aircraft, notably the famed Hawker Hurricanes, were being built for the Allied forces overseas.During the war, MacGill was credited with introducing mass production techniques to the aviation industry, modifying the Hurricane for winter use and establishing standards for test pilot reporting. In the post-war years, she continued to break new ground as the first woman aeronautical engineer to open a consulting business and the first to serve as the chair of a United Nations aviation technical committee. In the latter capacity, she led in the drafting of the first airworthiness regulations for the new International Civil Aviation Organization.

In Canada, MacGill was known as the first woman in her country to receive a degree in electrical engineering, in 1927 from the University of Toronto; the rst woman to be admitted as full member in the Engineering Institute of Canada; and the first woman to receive the profession’s prestigious Gzowski Medal, as well as many other honours. In the United States, at the University of Michigan, she became the first woman anywhere to earn a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. The year was 1929.

Comfortable on both sides of the border, MacGill returned to the U.S. and continued to blaze trails as a woman doctoral student at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), amidst some of her profession’s brightest lights. The list of professional achievements and recognitions would have alone marked MacGill as worthy of celebration, particularly as a pioneer for her gender.

But there are other, even more moving features of MacGill’s life and story that were known to her colleagues and continue to encourage others to this day.

Overcoming great personal odds

On the eve of her 1929 graduation from Michigan, 24-year- old MacGill fell ill to awaken the next morning fully paralyzed from the waist down. She had been struck by a form of polio and would spend the next three years con ned to bed and a wheelchair at her parents’ Vancouver home. Her plans for a wedding and the launch of her engineering career were cancelled, and she had reason to wonder whether her personal and professional lives would ever recover. But she kept her career aspirations alive by writing journal and magazine articles on aviation from her bed, and slowly she regained enough strength to use metal walking sticks to get around.

As soon as she was self-sufficient, she moved back east to MIT, and then to the string of industry projects that made her mark and reputation in engineering. Ironically, the high point of her recognition by SWE in 1953 was followed by a serious setback a few months later. She slipped on a rug and broke her good leg, plunging her back into a wheelchair and into a series of ill-advised surgical treatments that threatened to disable her permanently. Again, she recovered, and again she used the enforced convalescence to write. This time, she produced a biography of her late mother, Helen Gregory MacGill, the first woman in Canada to receive the title of “judge.”

Another turning point

The experience of writing My Mother, the Judge stirred new passions in MacGill, prompting her, now nearing the age of 50, to plunge into the cause of women’s rights in a more energetic way. This led to her election as national president of the Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs, and subsequently, to membership as effective vice-chair of the landmark Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada in 1967. Through the Royal Commission, MacGill influenced laws and national policies, often through words that were reflected in federal legislation, for decades to follow.

Her death in 1980, at the age of 75, was indirectly caused by her disability. At the time, many felt her life had been cut short. It was clearly full, however, and its impact has been enduring.

Those who wonder where MacGill found the strength and motivation to persist through disabling illness; periods of economic, social and military struggles; and gender bias that denied her some professional opportunities, often point to the role model of her mother, her sister’s support, and the love of her husband, Bill Soulsby, and her stepchildren.

Those who knew MacGill best also suggest that she was buoyed through hardships and challenges by what her colleagues described as a “rare sense of humour and scintillating sense of fun.”

The model of having fun while striving to improve the world and to do one’s personal best may, in fact, be MacGill’s greatest legacy to her profession, her gender and humanity.