This gallery is Part 5 of an eight-part series, Engineering Experiential Learning, running throughout spring and summer 2015.

On May 10, more than 250 engineering students from 12 universities across Canada converged in Toronto to make the unfloatable float. They raced canoes made of concrete — boats they designed and built themselves — for the 2015 Canadian National Concrete Canoe Competition (CNCCC).

Hosted by U of T Engineering, the competition involved students from a diverse range of engineering disciplines, including civil, mechanical, industrial and materials science. These teams spent the last year constructing their own canoes, with the CNCCC serving as a showcase of their technical, creative and collaborative abilities.

See the canoes in action:

“The CNCCC not only provides teams an opportunity to share a year’s worth of hard work with the public, but it offers a great chance for us to showcase the city and its multiculturalism with students from across the country,” said U of T civil engineering graduate Nigel Fung (CivE 1T5 + PEY), the commissioner of this year’s competition.

Global News, CTV News, CBC Radio, CP24 and Fairchild TV joined for the action.

Researchers at the University of Toronto design diagnostic chip to reduce testing time from days to one hour, allowing doctors to pick the right antibiotic the first time

We live in fear of ‘superbugs’: infectious bacteria that don’t respond to treatment by antibiotics, and can turn a routine hospital stay into a nightmare. A 2015 Health Canada report estimates that superbugs have already cost Canadians $1 billion, and are a “serious and growing issue.” Each year two million people in the U.S. contract antibiotic-resistant infections, and at least 23,000 people die as a direct result.

But tests for antibiotic resistance can take up to three days to come back from the lab, hindering doctors’ ability to treat bacterial infections quickly. Now PhD researcher Justin Besant and his team at the University of Toronto have designed a small and simple chip to test for antibiotic resistance in just one hour, giving doctors a shot at picking the most effective antibiotic to treat potentially deadly infections. Their work was published this week in the international journal Lab on a Chip.

Resistant bacteria arise in part because of imprecise use of antibiotics—when a patient comes down with an infection, the doctor wants to treat it as quickly as possible. Samples of the infectious bacteria are sent to the lab for testing, but results can take two to three days. In the meantime, the doctor prescribes her patient a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Sometimes the one-size-fits-all antibiotic works and sometimes it doesn’t, and when the tests come back days later, the doctor can prescribe a specific antibiotic more likely to kill the bacteria.

“Guessing can lead to resistance to these broad-spectrum antibiotics, and in the case of serious infections, to much worse outcomes for the patient,” says Besant. “We wanted to determine whether bacteria are susceptible to a particular antibiotic, on a timescale of hours, not days.”

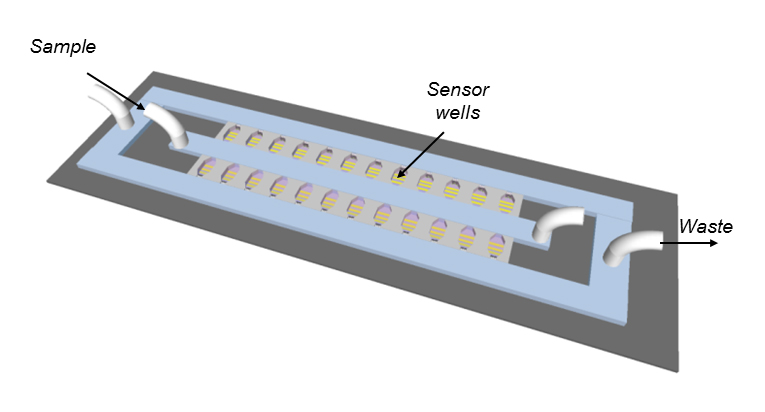

The problem with most current tests is the time it takes for bacteria to reproduce to detectable levels. Besant and his team, including his supervisor Professor Shana Kelley of the Institute for Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineering and the Faculties of Pharmacy and Medicine, and Professor Ted Sargent of The Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, drew on their collective expertise in electrical and biomedical engineering to design a chip that concentrates bacteria in a miniscule space—just two nanolitres in volume—in order to increase the effective concentration of the starting sample.

They achieve this high concentration by ‘flowing’ the sample, containing the bacteria to be tested, through microfluidic wells patterned onto a glass chip. At the bottom of each well a filter, composed of a lattice of tiny microbeads, catches bacteria as the sample flows through. The bacteria accumulate in the nano-sized well, where they’re trapped with the antibiotic and a signal molecule called resazurin.

Living bacteria metabolize resazurin into a form called resorufin, changing its electrochemical signature. If the bacteria are effectively killed by the antibiotic, they stop metabolizing resazurin and the electrochemical signature in the sample stays the same. If they are antibiotic-resistant, they continue to metabolize resazurin into resorufin, altering its electrochemical signature. Electrodes built directly into the chip detect the change in current as resazurin changes to resorufin.

“This gives us two advantages,” says Besant. “One, we have a lot of bacteria in a very small space, so our effective starting concentration is much higher. And two, as the bacteria multiply and convert the resazurin molecule, it’s effectively stuck in this nanolitre droplet—it can’t diffuse away into the solution, so it can accumulate more rapidly to detectable levels.”

“Our approach is the first to combine this method of increasing sample concentration with a straightforward electrochemical readout,” says Professor Sargent. “We see this as an effective tool for faster diagnosis and treatment of commonplace bacterial infections.”

Rapid alternatives to existing antibiotic resistance tests rely on fluorescence detection, requiring expensive and bulky fluorescence microscopes to see the result.

“The electronics for our electrochemical readout can easily fit in a very small benchtop instrument, and this is something you could see in a doctor’s office, for example,” says Besant. “The next step would be to create a device that would allow you to test many different antibiotics at many different concentrations, but we’re not there yet.”

Originally published in the Spring 2015 issue of Edge Magazine.

Have you ever been on a plane and marvelled over the fact that a 400-ton hunk of metal can get off the ground? As you peered out the window at the wing flaps, you probably thought about how the miracle of flight has something to do with the laws of physics. Or maybe, temporarily deafened by the roar of the jet, you credit the internal combustion engine.

All that may be true, but you also have something else to thank for getting you safely and speedily to your destination: coating.

The landing gear, the engine, even the windshield wipers — everything is coated with substances to allow the plane and its parts to withstand heat, fight corrosion and repel water.

It’s true in daily life, too. Your enamelled bathtub, your non-stick pan, your eyeglasses, even the paint on your walls — coatings are all around you. And their manufacture is a multi-billion dollar industry that is constantly innovating to create products that improve performance while protecting health and the environment.

For 20-plus years, mechanical engineering professor Javad Mostaghimi (MIE) and his colleagues at the Centre for Advanced Coating Technologies have been conducting basic research into how coatings work and testing and developing new coatings as well as technologies for applying them.

Take those airplane engines. “According to thermodynamics,” Mostaghimi says, “if you run an engine at higher temperatures, you get better efficiency. We can run engines at higher temperatures if the materials they’re made of can withstand those temperatures. The challenge is that the materials that can withstand those temperatures are not good for manufacturing. Ceramic, for example, can withstand high temperatures, but it is brittle. You can’t use it to build things. But you can put a thin layer of it on other things that are good for manufacturing.”

Coating, says Mostaghimi, used to be more of an art. His group is bringing scientific rigour to the field.

“The basic, fundamental building block of coating is the impact of droplets on surfaces,” he says, so his team models and photographs what happens when droplets hit surfaces.

But, he says, “this is a technology that should be applied.”

And apply it they do, working with industrial partners to solve problems and improve processes. Based out of a lab packed full of various machines and tools to test different sprays and surfaces, they have undertaken all kinds of challenges, including:

- Developing coatings for reactors that process waste from nuclear power generation and make it into hydrogen.

- Improving the infrastructure that burns municipal waste to make the process more environmentally-friendly.

- Developing coatings for valves in factories to make them much less vulnerable to corrosion.

Coating, says Mostaghimi, may be invisible in most cases, but that’s just because it’s “an enabling technology.”

In other words, you don’t notice it because it’s doing its job.

An electrical and computer engineering professor and an alumna who has become a leading mining executive are among those honoured by this year’s Engineers Canada awards:

- Professor Jonathan Rose (ECE) received the Medal for Distinction in Engineering Education for his exemplary contributions to engineering teaching; and,

- Samantha Espley (Geo 8T8) received the Award for the Support of Women in the Engineering Profession for her engineering excellence and outstanding support of women in the engineering field.

“Jonathan Rose and Samantha Espley are remarkable examples of how U of T engineers pursue excellence in different disciplines,” said Dean Cristina Amon. “Not only are they experts in their respective fields, but they also continue to encourage innovation, entrepreneurship and diversity in the next generation of engineering leaders. On behalf of the Faculty, I extend my heartfelt congratulations to Jonathan and Samantha and express my gratitude to Engineers Canada for recognizing these valuable contributions.”

About Jonathan Rose

Joining the Faculty in 1989, Professor Jonathan Rose is well known for teaching his students through engineering design, where he encourages them to identify problems and then apply engineering concepts to build new technologies that solve them. He pioneered the creation of the course Digital Systems ECE 241, which gives students experience building and designing at the start of their second year, much earlier than other programs.

In 2011, Rose started the graduate course Creative Applications for Mobile Devices. The course brings together graduate student programmers — many of whom hail from engineering and computer science — to work with students from other fields across campus to create useful smartphone apps. The extremely popular course has already resulted in apps for surgery, museum navigation, asymmetric walking analysis, pain control, driving measurement, child medication dose control, high school education and addiction management.

Rose has successfully commercialized his own innovations in computer chip design, and is also passionate about incorporating entrepreneurship into the curriculum. In 2004, he founded the Engineering Entrepreneurship Seminar series to bring in guest speakers to share the story of their companies and inspire students to follow in their footsteps. Rose serves as the director of the Engineering Business minor, which he helped to develop, and was a key player in the creation of The Entrepreneurship Hatchery. Rose has also made significant contributions to engineering education beyond Canada through his role in the creation of the PhD program at the Addis Ababa Institute of Technology.

Rose’s teaching style occasionally incorporates elements of improv theatre, such as asking students to shout out answers simultaneously. This technique helps students overcome inhibitions and makes large, early-year classes feel more intimate. He has received the The Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering’s teaching award four times and won the Faculty Teaching Award — the Faculty’s highest teaching honour — in 2012. In 2014, Rose received the University of Toronto Faculty Award, presented to a faculty member from across the University who consistently demonstrates excellence in both teaching and research endeavours.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4oPagA47FEc&w=560&h=315]

About Samantha Espley

Since completing her degree at U of T Engineering, Samantha Espley has moved quickly through roles of increasing responsibility at Vale (formerly Inco) and previously with Glencore (formerly Falconbridge). She is currently general manager of the Mines and Mills Technical Services Department in Vale’s Ontario Operations, leading a multidisciplinary group of more than 200 engineers, geologists, metallurgists and technologists. She has also published and presented over 60 papers, reports and publications, with topics ranging from underground mine designs and automation systems to the role of women in the mining industry.

Ms. Espley is a founding member of Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) and has held leadership roles with WISE, the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (CIM), Professional Engineers Ontario (PEO) and the Canadian Mining Research Network (CAMIRO). She has been a keynote speaker at numerous events, such as the Ontario-wide university initiative Go Eng Girl (for young women in grades seven to 10), WISE Gearing Up sessions (for high school students), Science North and WISE Fireball events, as well as Science Olympics (for girls in grades four to eight) and PEO Job Shadowing events.

In recognition of her achievements and contributions to the engineering profession, Espley has received the International Women’s Week Award, the CIM Distinguished Service Medal, the U of T Engineering 2T5 Mid-Career Award and the Trailblazer Award from Women in Mining Canada.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ObQiA4Xwqpg&w=560&h=315]

Originally published in the Spring 2015 issue of Edge Magazine.

According to recent studies, texting while driving has surpassed drunkenness as the leading cause of death for teen drivers. But even as public service campaigns plead with drivers to relinquish their devices, cars are increasingly loaded up with GPSs, infotainment systems, dash cams and other on-board tech.

Cars themselves are becoming devices of distraction.

As vehicles get brainier, auto manufacturers have turned to university researchers to find ways to reduce, rather than exacerbate, distracted driving. Counterintuitively, that can mean turning driving into a kind of game.

“If your eyes have been off the road for a certain number of seconds, we’re going to provide you with real-time warnings. We know that helps,” says Birsen Donmez (MIE), an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical & Industrial Engineering who researches human-car interactions. “But we’re also experimenting with a gamification interface to motivate drivers to decrease their distraction.”

Using eye tracking, proximity sensors and other measurements, her lab generates post-trip reports on a driver’s performance. Drivers can compare their records against those of their peers or general society to see how they stack up — turning safe driving into a competitive sport.

“We also try to give people badges like in a game,” Donmez says. “‘In this portion of the drive, you were safe, your driving performance was good.’ This may help change the intrinsic motivation of the driver.”

She has been running tests both in simulators and on the road. Toyota Canada donated a Rav 4 to the project, which Birsen’s lab is tricking out with sensors and data recorders. The car manufacturer also supports her research financially through the Toyota Collaborative Safety Research Center (CSRC). Reflecting the complexity of modern car-making, the CSRC supports research that explores major issues like safety, rather than focusing on developing a specific new widget. Manufacturers like Toyota have begun to recognize the value in supporting research whose outcome is not known.

“Dr. Donmez’s research could eventually find its way into production,” says James Foley, the senior principal engineer at CSRC. “Once the project is completed and we know the benefits it can offer to encourage safe driving and minimize driver distraction, Toyota can consider how to best incorporate them into a car.”

Donmez says the game elements of her research will likely be most effective with risk-unaware or non-risk-averse drivers. (That’s code for teenagers.) Real-time warnings may matter more to older drivers who have declines in their attentional abilities.

Of course, she is wary of designing a feedback system that becomes a distraction unto itself.

“With something like a single alert that comes up if your eyes are off the road, the meaning is clear,” she says. “But with more complex displays we want to ensure that people’s eyes aren’t off the road for more than two seconds.”

Donmez’s partnership with Toyota concludes later this year, but the CSRC has announced a new round of funding. Her lab is in contention for follow-up projects, also aimed at ensuring that cars’ brains don’t mess up the brains of their drivers.

The word ‘drone’ often conjures up invasive images of military aircraft, but if Professor Hugh Liu of the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies (UTIAS) has his way, that perception is about to change.

Liu has just received $1.65 million from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to train 150 new experts in the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for a variety of useful purposes, from agriculture to environmental monitoring.

Ed Holder, Canada’s Minister of State for Science and Technology, shared the news today at UTIAS. Liu’s project is one of 17 from across Canada to receive a total of $28 million through NSERC’s Collaborative Research and Training Experience (CREATE) Program this year.

“This grant will allow us to work closely with industry partners to explore new applications in this emerging market,” said Liu. “It will give our students the opportunity to get practical experience and to prepare themselves to be the leaders in the field.”

As founder of the Flight Systems and Control (FSC) Research Laboratory at UTIAS, Liu and his team are experts in autonomously controlled flight. They design computer algorithms similar to those used in the autopilot software for commercial aircraft.

For example, a passenger plane contains an altimeter that measures how high the aircraft is above the ground. The algorithm would take this input data and use it to determine how much to boost or cut the engines in order to maintain a constant cruising altitude.

While commercial flights are important, Liu’s algorithms designed for UAVs can handle much more sophisticated inputs. For instance, one recent project with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources outfitted UAVs with thermal cameras, tuned to infrared light given off by hot objects.

Liu and his team designed algorithms that would enable the UAVs to find the edge of the blaze and fly along it. In this way, UAVs could help track the extent and spread of forest fires much more accurately than is currently possible, a boon to firefighters everywhere.

Another recent innovation was the creation of algorithms for synchronized flight. This allows a swarm of drones to sense each other’s location and to fly as a coherent unit.

Flying in formation is critical as many commercially-available drones are too small to carry large payloads. If they can act together as a team, with each UAV carrying different sensors or pieces of a deliverable package, they could achieve more than by flying individually.

Liu and his team have already received a patent for the motion synchronization, and were recently honoured among of U of T’s “Inventors of the Year”. Liu and former graduate students Mingfeng Zhang (AeroE PhD 1T3), Henry Zhu (AeroE MASc 1T4) and Everett Findlay (AeroE MASc 1T1) have created a spinoff company, Arrowonics Technologies Ltd., to commercialize the technology.

“With its emphasis on preparing graduate students for careers in industry, government and academia, the CREATE program is of tremendous benefit to the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies and the Canadian academic research community,” said David Zingg, director of UTIAS. “It facilitates fundamental, long-term research while at the same time enabling the universities to educate graduates who will be ideally placed to bring such cutting-edge research to fruition.”

Other possible applications of UAVs include scouting for mineral deposits or other natural resources, monitoring pipelines or railways for damage, checking up on crops, applying fertilizers and much more.

“Thanks to a combination of technology, timing and demand, I think we’re seeing the beginning of a golden age in the development of UAVs,” said Liu. “As users in commercial and consumer applications start to see the potential of drones, they will need engineers who are deeply familiar with the technology. This is what this grant will allow us to create.”