Leading up to International Women’s Day on March 8, U of T Engineering is celebrating some of our remarkable female alumni, faculty and students. These women are inspirational role models who are “making it happen” in engineering and beyond.

Whether it’s combatting climate change, enhancing biomedical technologies or improving urban infrastructure, engineers are solving global challenges and making a positive impact on our world.

Approaching these problems often requires diverse perspectives and multidisciplinary collaborations. And yet, as of 2013, women accounted for just 11.7 per cent of all professional engineers in Canada.

At U of T Engineering, we celebrate the diversity of our students. With 30.6% female first-year enrolment—the highest in Ontario—we are proud to share the successes of our remarkable students as they continue to inspire each other and enrich our culture of excellence.

Here are 10 students, selected by their departments for their academic and co-curricular achievements, who share why they chose engineering, and why it’s the perfect fit.

Chandini Chandrabalan (ECE 1T7)

In high school, many of Chandini Chandrabalan’s math and physics teachers discouraged her from engineering because they thought it would be too difficult. But Chandrabalan wasn’t deterred. Her interest in sustainability technologies led her to a degree electrical and computer engineering.

In high school, many of Chandini Chandrabalan’s math and physics teachers discouraged her from engineering because they thought it would be too difficult. But Chandrabalan wasn’t deterred. Her interest in sustainability technologies led her to a degree electrical and computer engineering.

“Whenever you’re passionate about something, there’s nothing really that can stop you,” she said.

Now Chandrabalan volunteers as a mentor to other students.

“I always tell them the technical things like math – that’s something you can learn. If you’re a logical thinker, you’re creative by nature and you have a critical eye for the world around you, that’s something inherent within you, and not necessarily something you can learn.”

“Students considering engineering: look within yourself and think about how you learn and what you like doing. It’s not necessarily about whether you’ve played with a circuit board or if you’re not keen on computers. Stuff like that can always come later.”

Chandrabalan says it’s particularly important that women participate as engineers.

“We are literally half of the population,” she said. “Engineers are at the forefront of how society operates.”

Marina Curak (MechE 1T6)

For Marina Curak, the decision to go into engineering came at the last minute, even though she had always loved science.

For Marina Curak, the decision to go into engineering came at the last minute, even though she had always loved science.

“Initially I was applying to all business programs. That’s what my parents wanted me to do,” she explained.

She applied to engineering just in case and, in the end, decided that was what she truly wanted to do. Curak’s older sister, who was studying civil engineering at U of T at the time, helped with her decision.

“My sister opened my eyes to see what engineering can do,” said Curak, now in her third year of mechanical engineering.

She exclaimed that she is “200 per cent” happy with her decision to enrol in engineering. “I love that the possibilities are limitless.”

With a passion for the environment, Curak is now participating in the U of T Supermileage Team, preparing for a competition where teams of students design and race electric cars. The team is working on a dynamic controller that will maximize efficiency for the 2016 race.

Fan Guo (TrackOne 1T7)

Not everyone realizes they’re destined for engineering at a young age, but Fan Guo is glad she did.

Not everyone realizes they’re destined for engineering at a young age, but Fan Guo is glad she did.

“I was lucky enough that my parents always encouraged me when I showed an interest in science,” said Guo, who now studies electrical engineering.

In grade seven, her science teacher urged her to participate in National Engineering Week. Tasked with the relatively simple challenge of building a thermos, Guo’s interest became a spark that would ignite into passion.

“It was my first taste of what the world of engineering could be like,” said Guo. “I went again the second year and I decided this might be something I want to do in the future.”

Guo loves how engineering often involves collaborating with people from different disciplines and perspectives.

“The way I approach a problem could be very different from the way a person with a mechanical engineering background may approach a problem. But in the end, it’s all the same. We are all looking for a solution.”

Lauren Howe (IndE 1T6)

Lauren Howe chose to study industrial engineering because of the diverse range of jobs she could pursue after graduation.

Lauren Howe chose to study industrial engineering because of the diverse range of jobs she could pursue after graduation.

“I think I have a pretty balanced mindset between an analytical thought process and being able to look at the bigger picture, and how actions can impact society,” she said, and that balanced mindset has helped her excel in more than just academics.

Currently, Howe is the In-Arena host for the Toronto Maple Leafs, as well as the Executive Vice President of the University of Toronto Sports and Business Association.

Howe was also named Miss Canada Teen in 2011. She asserts her main focus during the competition was on her studies and athletics, and that the same qualities that helped her win, such as drive, competitiveness and perfectionism, are also qualities that make a good engineer.

“When you pursue things that you are passionate about, that passion comes through and you will find success in whatever field you choose.”

Katlin Kreamer-Tonin (EngSci 1T6)

For Katlin Kreamer-Tonin, a third-year engineering science student with a biomedical specialization, engineering is an opportunity to see concrete results from her work.

For Katlin Kreamer-Tonin, a third-year engineering science student with a biomedical specialization, engineering is an opportunity to see concrete results from her work.

As a part-time research and development intern at Spinesonics Medical, she is helping create a new device to improve spinal fusion surgery.

“I think the most rewarding part [of engineering] is that you can can see the impact of your work,” she said.

Although she hasn’t completed her degree yet, Kreamer-Tonin is already experiencing the global opportunities that often materialize in engineering. This summer she is working on a 12-week research project at King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi in Thailand, designing a smart home for the elderly.

“There are so many different opportunities if you are a young engineer,” said Kreamer-Tonin, who is 21 years old. “You can go in any direction you want to and you get to shape society and technology.”

She noted that it’s especially important for women to contribute as engineers because of how important diverse teams can be in engineering.

Jacqueline Murdock (ChemE 1T5)

Jacqueline Murdock says she was always good at math and science, but what really attracted her to engineering was the opportunity to develop tools that can help her solve some of the world’s problems.

Jacqueline Murdock says she was always good at math and science, but what really attracted her to engineering was the opportunity to develop tools that can help her solve some of the world’s problems.

Murdock is now completing her fourth and final year in chemical engineering, but she is not the first engineer in her household. Her father is a chemical engineer as well.

“The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree,” said Murdock, laughing.

But as she pointed out, chemical engineering today offers much more diverse opportunities than when her father started his career.

“It’s not as straightforward as it was before.”

Nearing graduation, Murdock is excited to join the energy sector and contribute new methods to mitigate negative impacts on the environment. Initially, she aims to gain some technical experience, but eventually wants to tap into the policy side of engineering.

“You can have the technology and it can be a really great idea, but it needs to have funding and support to be able to grow.”

Parisa Najafi (MSE 1T6)

While in her first year, materials science and engineering student Parisa Najafi was tasked with discovering why ice affects similar trees differently. As she examined the microscopic structures of birch and quaking aspen, Najafi developed a fascination of the natural world that has informed her education ever since.

While in her first year, materials science and engineering student Parisa Najafi was tasked with discovering why ice affects similar trees differently. As she examined the microscopic structures of birch and quaking aspen, Najafi developed a fascination of the natural world that has informed her education ever since.

“Nature makes the best classroom,” she said. “It’s hands-on, it’s dynamic, and its designs are usually more elegant and efficient than our own. Lucky for us, nature hasn’t patented anything yet.”

Inspired by her environment, Najafi, now in her third year of studies, pursued an opportunity as a research associate with nanOntario, an outreach program aimed at teaching high school students about bio-inspired technologies. The program brings nature into the classroom as both a teaching tool and an inspiration for students.

“We have the responsibility as engineers to think critically about these issues because we have the skills to innovate and drive positive change.”

Nataliya Pekar (TrackOne 1T7)

As someone who tends to enjoy a range of academics, Nataliya Pekar was initially undecided about what she wanted to do in school. Ultimately, she chose engineering because she saw it as an opportunity to design and make real-world change to systems and infrastructure.

As someone who tends to enjoy a range of academics, Nataliya Pekar was initially undecided about what she wanted to do in school. Ultimately, she chose engineering because she saw it as an opportunity to design and make real-world change to systems and infrastructure.

“I just felt like I could make more tangible differences through engineering, especially in terms of sustainability,” she explained.

After completing Track One, a general first-year introduction to engineering, Pekar chose to pursue civil engineering.

“In certain engineering disciplines, you look at individual objects or designs. But in civil engineering, I like that you are often designing an entire system, like a wastewater treatment plant or a system for all of the transportation in Toronto. It impacts so many different people, and you have to take into consideration so many different impacts and problems.”

She recently put her skills as an engineer to work at the Ontario Engineering Competition, taking home second place in the consulting category. Pekar and her team went on to compete in the Canadian Engineering Competition in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador.

Yoko Yanagimura (MinE 1T6)

The thought of being an engineer didn’t cross Yoko Yanagimura’s mind at a young age.

The thought of being an engineer didn’t cross Yoko Yanagimura’s mind at a young age.

“All my life I thought I was going to be a biologist,” she said now.

She says a major reason for that is that not enough high school students are made aware of engineering as an option.

“When you’re in high school, you don’t learn about engineering. You learn about set subjects that don’t cover all of what you can study in university.”

After attaining her degree in her biology, Yanagimura decided to pursue studies in mineral engineering. She enjoys the ethical and social aspects of the job. Plus, she has a chance to significantly impact projects and be a part of an important process. She finds mineral engineering particularly exciting because this industry is “at the forefront of environmental management.”

“I can’t believe how much I love this,” said Yanagimura. “I wish I could have studied it earlier.”

Olesya Zhychkovska (CivE 1T6)

Even though Olesya Zhychkovska’s father is an engineer, his career did not directly influence her career path.

Even though Olesya Zhychkovska’s father is an engineer, his career did not directly influence her career path.

“It was his character traits that inspired me,” she explained. “Not the engineering itself, but the kind of person he was.”

After gaining her father’s work ethic and passion for finding answers, Zhychkovska chose to pursue a degree in civil engineering.

“I don’t like to give up. If I’m challenged with something, I won’t give up until I find a solution.”

She says engineering is certainly challenging at times, but also rewarding. “Seeing results only encourages and motivates me to work harder,” said the 22-year-old.

Her advice to other young aspiring engineers is to, “Learn to be confident. If you know that this is truly what you want to do in life, then never let anything bring you down or make you divert from this path.”

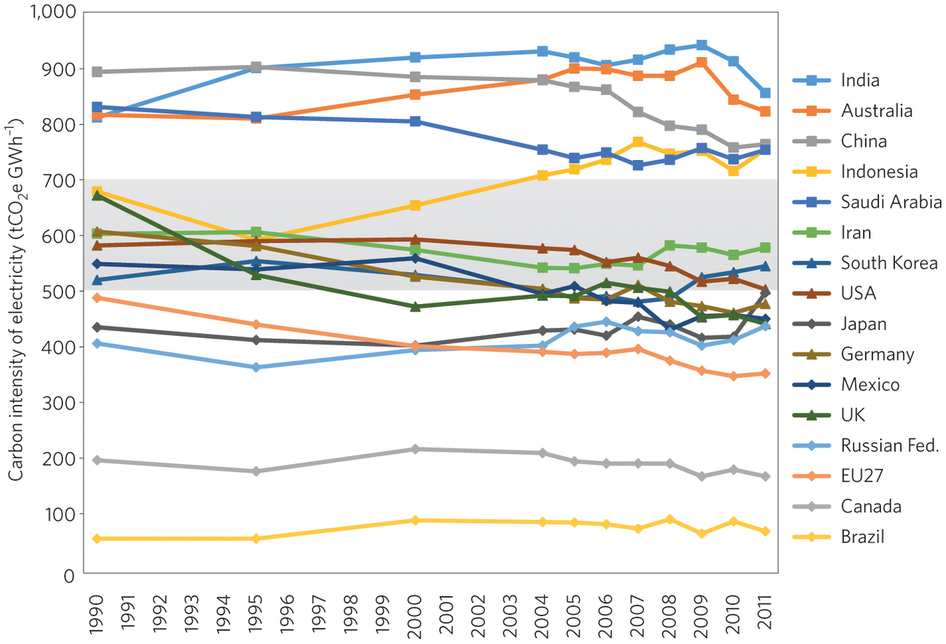

Whether it’s swapping your car for an electric vehicle, or your natural gas furnace for geothermal heating, transitioning from fossil fuels to electric-powered technology is widely believed to be the best way to lower carbon emissions.

But according to U of T civil engineer Chris Kennedy (CivE), knowing where the electricity comes from to power those “eco-alternatives” is critical. If that electricity comes from burning oil and coal, it might mean that green alternatives aren’t that green after all.

Kennedy’s study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, proposes a new decision-making threshold for when to move from fossil fuel technology to electric power (called electrification), and at what point that move may increase or lower carbon emissions.

Although regions may welcome “green” technology like electric vehicles, high-speed rail and geothermal heating, they aren’t green if the electricity to power them creates even more carbon emissions than their oil-driven counterparts.

For electrification to lower emissions, Kennedy says that a region needs to produce its electricity at a rate below his threshold: approximately 600 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per gigawatt hour (GWh). This means that for every gigawatt hour of electricity generated (the power needed to run about 100 homes for a year), less than 600 tons of greenhouses gases (measured as “CO2 equivalent”) can be emitted.

If a region’s electricity production exceeds this 600-ton threshold, such as in countries like India, Australia and China (as shown below in Figure A), electrification could actually increase carbon emissions and accelerate climate change.

Countries such as these generate much of their electricity using coal, which he says produces about 1,000 tons of CO2 equivalent per GWh—nearly double the suggested threshold. Natural gas, on the other hand, produces 600 tons, and hydropower and nuclear energy produce nearly zero.

“You could speculate that incorporating electrified technologies such as high speed rail in China may not lower overall emissions,” says Kennedy. “It might even be more carbon friendly to fly.”

Kennedy employed an industrial ecology approach to dig into the data from four previous studies—including one from the International Energy Agency and others from Canada, the U.S. and countries in Europe.

As a nation, Canada’s electricity does not produce very much carbon in comparison to other regions. It ranks low on the list, at just under 200 tons of CO2 equivalent per GWh. “Despite that many believe our power is generated using fossil fuels from Alberta, most of Canada’s electricity mix comes from hydropower and nuclear facilities,” Kennedy says.

But when he zoomed in on certain regions in Canada, some of this good news changed. In a previous study, he compared the use of “green” geothermal heat pumps (used in homes) versus natural gas furnaces across different provinces. He found that the pumps were more eco-friendly in Ontario and British Columbia—owing to nuclear and hydropower—but in coal-dependent Alberta, it was greener to stay with a natural gas furnace.

In his recent paper, Kennedy also cites a study that found using plug-in electric vehicles emitted less carbon when used along the west coast of the United States, but produced the same, if not more, carbon when used in the Midwestern U.S.

Why does this threshold matter?

“Looking at overall carbon emissions of one country or a group of countries can only get you so far,” says civil engineering PhD student Lorraine Sugar (CivE MASc 1T0, PhD 1T8), who worked as a climate change specialist for the World Bank for nearly five years. “It’s hard to track progress and set goals internationally, while holding regions accountable. Having a specific and measurable target like this threshold is incredibly important, especially leading into the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris later this year.”

According to Kennedy, this threshold puts a marker down in a policy arena where none has existed before—and it isn’t just valuable for government.

“It reframes part of the climate change debate by encouraging individuals around the world to better understand where their electricity is coming from before they adopt supposedly eco-friendly technologies,” he says. “And even more, it incites them to understand how much carbon is emitted during the entire life cycle of those technologies—from their ongoing operation to their manufacture and disposal.”

He recommends people search for their local government energy agencies to find out how electricity is generated. If it is largely coal, then electric-powered technologies like ground-source heat pumps or electric vehicles may not be the most eco-friendly alternatives. On the national and international stage, he hopes governments do the same research when developing environmental policies and incentives.

“Canada’s three largest cities—Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver—have some of the lowest carbon emissions from electricity generation in the world,” says Daniel Hoornweg (CivE PhD), an associate professor at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology and a current U of T engineering PhD student.

“This threshold helps politicians make smarter energy decisions,” says Hoornweg, who recently retired from the World Bank after nearly 20 years in the urban sector. “Why aren’t we making better use of these advantages to electrify our transportation modes? And why are we so focused on one or two energy projects (like a pipeline) instead of working on a more comprehensive U.S.-Canada energy agreement that could better leverage our energy strengths?”

(Photos: Shutterstock, VinceFL, Vladimir Jovanovic, Watt Energy Saver)

Leading up to International Women’s Day on March 8, U of T Engineering is celebrating some of our remarkable female alumni, faculty and students. These women are inspirational role models who are “making it happen” in engineering and beyond.

Since 1873, U of T Engineering’s alumni community has grown to more than 50,000 worldwide, including innovators in medicine, sustainable energy, education and urban development.

Here are eight female alumnae who are making an impact on our world, from the outer reaches of the universe to the inner workings of the human brain. They are pushing boundaries and blazing a trail for generations of engineers to come.

Joelle Javier (MSE 1T0)

Engineer-in-Training, Technical Standards and Safety Authority

Not many engineers get to add “thrill-seeker” to their resume, but for Joelle Javier, it’s essential. As a safety specialist in amusement park rides for Ontario’s Technical Standards and Safety Authority (TSSA), she makes sure devices stand up to diehard adrenaline junkies.

“I get to imagine the worst thing a person could do to make the experience more fun,” she says. “I try to push the boundaries of the design, and then test it for safety.”

Javier reviews design submissions for new rides and inspects existing installations at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE), Canada’s Wonderland and other parks. Relying on her knowledge of materials science—and especially her training in failure analysis at U of T—she pinpoints the potential causes of equipment malfunctions. She also meets with international committees to develop standards for the newest thrills, like zorbing and ziplining.

“The industry is growing and there are gaps in expertise,” she says. “In the future, I’d like to combine my skills and knowledge to design new rides.”

Catherine Lacavera (ECE 9T7)

Director of Intellectual Property Litigation, Google

She’s been called “Google’s secret weapon in the smartphone wars” and named one of Fortune Magazine’s 40 Under 40 for 2013. But before she became one of the tech industry’s most powerful women, attorney Catherine Lacavera got her start at U of T Engineering. She earned her B. Sc. in Computer Engineering in 1997, followed by an MBA and law degree, also at U of T.

Since she was hired at Google in 2005, she has led her legal team to victory in many multi-million dollar litigation matters in the U.S. and internationally, including Viacom’s copyright lawsuit against YouTube and the Apple, Microsoft and Oracle litigation directed at Android. She also advises on licenses and acquisitions, including the $12.5 billion purchase of Motorola Mobility. At any given time, she oversees more than 100 pending patent and intellectual property cases.

Loyal to her roots, Lacavera remains involved at ECE, serving on the faculty’s Board of Advisors since 2012.

Maryam Modir Shanechi (EngSci 0T4)

Assistant Professor, Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Southern California

Named one of Technology Review’s Top 35 Innovators under 35 for 2014, Maryam Shanechi ranks among the world’s most promising young brain researchers. She has been tapped to join the Obama BRAIN initiative, a $300 million brain mapping collaboration that has been compared to the Human Genome Project in scope.

A PhD graduate from MIT, Shanechi’s work with brain-machine interfaces combines technology with neuroscience to decipher the brain’s electrical signals, potentially allowing researchers to manipulate those signals to treat neuropsychiatric disorders like depression. It could also help paralyzed patients move robotic limbs using only their thoughts, and automate anesthesia using feedback from the brain during surgery.

She credits her undergraduate experience at U of T Engineering with giving her the tools to pursue her passion for neuroscience. “At U of T, I learned how to be an independent thinker and forge my own career path,” she says. “I got the best possible education as an undergrad, which prepared me well for graduate school at MIT.”

Camila Londono Ferroni (EngSci 0T7 + PEY, IBBME PhD 1T5)

PhD Candidate, Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, University of Toronto

A pioneering researcher in cell migration, Camila Londono Ferroni is the first author of a foundational study published February 2014 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Londono’s team discovered that, much like strangers in a crowd, cells in groups communicate by pushing each other as they move. Interestingly, these pushes come together to create long-range communication, which means the cells do not need to be connected to each other to move as a single unit. Her research could change our understanding of how the body heals wounds, how cancer metastasizes and other biological processes.

“The next step would be to try to understand how to make cells move more efficiently,” she says.

Londono says she is excited by the possibilities offered by the field of biomedical engineering. “As the population gets older, there is more need for problems to be solved,” she says. “This field has so much new ground left to cover.”

Rachelle McCann (ChemE 1T2 + PEY)

Consultant, Compass Renewable Energy Consulting Inc.

Over the next 50 years, renewable energy sources are expected to supply most of the world’s electricity requirements. To help Ontario’s solar, wind and biomass power developers meet the growing demands of the sustainable energy market, engineering grads like Rachelle McCann are offering their technical expertise and problem-solving acumen.

McCann’s firm, Compass Renewable Energy, provides support for companies involved in the province’s Feed-in Tariff contracts, which allow renewable energy providers to sell power to the grid at fixed prices. Among her many responsibilities, McCann monitors a portfolio of solar ground mount projects to ensure the materials used meet local content standards.

Her passion for the environment drives her enthusiasm for the job, and she enjoys the wide range of challenging projects. “I never settle into the same way of thinking or solving problems,” she says. “This creates an interesting work environment.”

Natalie Panek (UTIAS MASc 0T9)

Mission Systems Engineer, MDA Robotics and Automation

An aspiring astronaut and passionate advocate for women in science, Natalie Panek takes a no-holds-barred approach to everything she does. Whether she’s designing spacecraft, trekking in Patagonia or building and racing a solar-powered car across North America, her enthusiasm for adventure is contagious.

With MDA’s Robotics and Automation division, which created the original Canadarm, Panek is helping develop the next generation of technologies to support Canadian and international space missions. Her project portfolio includes a robotic tool to repair and refuel broken satellites, reducing the amount of debris in orbit. “If we can use hardware that’s already up there, it makes space exploration more sustainable,” she says.

Named one of Forbes’ 30 Under 30 for 2015, Panek is a popular speaker on female empowerment. She is involved with Cybermentor, an online program through the University of Calgary that allows young women to ask questions and engage with female mentors in STEM fields.

Caroline O’Shaughnessy (MIE 1T0 + PEY)

M.D. Candidate, University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine

As an undergraduate in Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Caroline O’Shaughnessy hadn’t originally considered a career in medicine. But when her extracurricular activities brought her into the world of first responders, she found her calling.

She started out as a volunteer with the University of Toronto Emergency First Responders, which began in 2006 as a small group of MIE students providing First Aid during Skule™ events (such as the famously full-contact Chariot Race). Eventually, they expanded their patrols to the entire campus, covering events and teaching CPR.

O’Shaughnessy credits her fellow Engineering students for their camaraderie, inclusiveness and work-hard, play-hard ethos. “It’s really easy to get involved, because everyone’s involved,” she says.

“Engineering teaches you how to think and work through problems,” she says. “I found that gave me a huge advantage in my clinical placements.”

Mary Alexander (CivE 1T3, MEng 1T4)

Structural Designer, Moses Structural Engineers

Working alongside architects, Mary Alexander designs wood and timber constructions, providing engineering assistance on a variety of new projects. Her firm, Moses Structural Engineers, has been involved with some of Canada’s most innovative wood builds, such as the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto and the TD Place Stadium in Ottawa.

Working alongside architects, Mary Alexander designs wood and timber constructions, providing engineering assistance on a variety of new projects. Her firm, Moses Structural Engineers, has been involved with some of Canada’s most innovative wood builds, such as the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto and the TD Place Stadium in Ottawa.

Recent changes to Ontario’s building code allow wood and timber construction up to six storeys, ushering in a new era of desirable mid-rise buildings. “Wood is a lot faster to go up, it’s lighter, and there are significant cost savings,” Alexander says. “It’s also more eco-friendly—it has a net zero or negative carbon footprint.”

All this adds up to more demand for skills like Alexander’s. As an undergrad in Civil Engineering, she became interested in building science and chose to further specialize with an M. Eng. in Structural Engineering.

“I love what I do, it’s basically my dream job,” she says. “As our infrastructure ages, there are huge opportunities for new grads.”

University of Toronto biomedical engineering professor Molly Shoichet (ChemE, IBBME) has been named the L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science North American laureate for 2015.

Already the only person ever elected to all three of Canada’s science academies, Shoichet is the innovative mind behind breakthroughs ranging from ‘space suits’ for fragile stem cells to polymer-based ‘vehicles’ that could let cancer drugs ‘drive’ to affected areas.

The award—which involves a $140,000 prize—recognizes accomplished women researchers and encourages more young women to enter science and technology careers. (A recent report from Engineers Canada revealed that only 18.3 per cent of undergrad engineering degrees in the country were awarded to women in 2013—an area U of T is changing with record-high female enrolment for 2014.)

“Since I can remember, my Mom encouraged me to have a profession,” says Shoichet. “I did well in math and science in high school and was lucky to be able to dream about what I could contribute. Now I’m following that dream for a living.”

Stem cell ‘space suits’ made of Jell-O

For Shoichet, the key to that dream lies in Jell-O-like materials called hydrogels —networks of polymer chains that swell in water, can thin and flow when forced through a needle, and then set almost immediately. These hydrogels allow stem cells or drugs a better chance of getting to and integrating into the parts of the body where they’re needed.

“If you have a series of wires that are all broken, just throwing in more wires won’t fix things,” says Shoichet. “In the nervous system, for example, we need those wires to be connected to a circuit to work…We need the stem cells to survive long enough to integrate, but we need the cells to integrate in order to survive.”

Shoichet and team have solved this chicken-and-the-egg dilemma with a delivery system that acts as a sort of space-suit, incorporating fragile stem cells in a hydrogel that has survival-promoting ‘life-support’ cells inside the gel. This enables the stem cells to survive long enough to give them a fighting chance to integrate—a stage to which most stem cells implanted into the body fail to reach.

Such transplants could someday lead to truly miraculous treatments for spinal cord injuries, stroke and blindness to name a few— where hydrogel-based ‘vehicles’ could transport specifically-engineered cell groups more safely directly to damaged tissue that needs repairing.

‘Driving’ polymer ‘vehicles’ to treatment sites

Shoichet and team are also designing polymers to deliver specially-engineered nano-scale drugs to specific areas of the brain and spinal cord, stimulating existing stem cells to mend damaged tissue.

To do this without damaging the brain or spinal cord, Shoichet and team take a hydrogel containing the stem-cell-stimulating drug and nano-spheres filled with an additional drug to slow the release of the stem-cell-stimulating drug and inject it directly on top the brain or spinal cord for a local, sustained release to the damaged tissue.

This allows the stem-cell-stimulating drug to be carefully laid onto the brain (or spinal cord), safely getting around the blood barrier (or the blood-spinal-cord barrier), beyond which the drug is able to act to promote repair.

“If I knew how complex the central nervous system was, I wouldn’t have gotten into this field,” Shoichet jokes, laughing. “But it’s this complexity that makes my field so exhilarating and full of promise.”

‘Seep-and-destroy’ cancer treatment

Cancer research caught Shoichet’s interest after a good friend of hers died of breast cancer 10 years ago. Now, Shoichet and team are creating materials that will deliver drugs directly to cancer cells, aiming to overcome some of the horrible side-effects of current cancer treatments.

To do so, they deliver potent drugs to the centre of a cancerous area where they disperse throughout that area and stay around long enough to kill cancer cells, leaving healthy cells largely untouched.

Riding inside the polymers that carry these drugs, nano-beads spread through cancer-stricken areas via the vascular system. At 1/1000 the thickness of a human hair, the beads are small enough to cross the leaky cancerous vasculature but large enough to stop at the more solid healthy vasculature.

Shoichet hopes that these discoveries and many others her team is working on – such as microscopic scaffolding that guides where cells will grow tissues for transplantation – will soon help improve our standard of living.

Culture of collaboration

When those real-world benefits come (some of Shoichet’s work has already been commercialized), she insists that it’s all been possible only through connections with hundreds of colleagues and students.

“Molly is a fantastic collaborator who never gives up on people or ideas,” says Dr. Cindi Morshead, colleague and Anatomy Chair at the U of T’s Donnelly Centre for Cellular + Biomolecular Research. “She just has such an incredible energy.”

The motto of The Shoichet Lab—“Solving Problems Together”—is evident in every aspect of the workplace she’s created: At the end of their time with the facility, students have their lab coats “retired” and hung on a wall of fame like the jerseys of iconic hockey legends.

“PhD and Masters students that come here to learn very quickly end up teaching me about what they’ve been tasked with becoming an expert on,” says Shoichet.

Like the time she and research students discovered that one of their hydrogels not only held its contents properly but the material it was made of itself was therapeutic to the tissues it was delivering drugs to.

“Sometimes discoveries are a slow progression, but that was a bit of an ‘ah-ha!’ moment,” says Shoichet. “When the gel didn’t seem to do anything bad and actually seemed to do something good, we stood back and said, ‘hey, we’ve really got something here.’”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hxOjfRAmZQQ

In addition to the honour for Professor Shoichet, U of T and Hospital for Sick Children researcher Dr Vanessa D’Costa received one of this year’s 15 L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Rising Talent grants for her research into new drug-resistant strains of salmonella.

U of T Engineering’s Mark Fox (MIE) believes smart cities need smart citizens.

On Feb. 10, 2015, the industrial engineering professor spoke to a capacity crowd at the Twenty Toronto Street Conference Centre about what it means for a city to be a “smart city” and the role that citizens must take in order to meet their service needs.

Fox’s talk was part of the ongoing U of T in Your Neighbourhood lecture series.

What is a smart city?

The concept of the “smart city” is a widely discussed topic in academia, with no single definition.

But Fox said a common characteristic of most smart cities is that they adopt a city-centred view, where it is the city’s (municipal government) responsibility to provide the services, information and anything else they think its citizens need.

He cited Rio de Janeiro as one example. In 2010, Rio’s mayor enlisted IBM to build its Rio Operations Center—an urban command centre with a bank of large digital screens where more than 30 municipal and state departments, plus private utility and transportation companies, monitor the daily activity of the city and potential crisis situations, including traffic, major events and natural disasters.

Fox was one of four U of T engineers who recently returned from India, where he joined U of T president Meric Gertler in discussions with thought leaders and policy makers about the role universities play in the development of smart cities. Last year, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, committed to building 100 smart cities throughout the country.

The citizen perspective

According to the Ontario Ministry of Finance, the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) is projected to be the fastest growing region in the province, with its population increasing by more than 45 per cent to reach 9.4 million by 2041.

“Where are we going to put these people; how are we going to connect them; and how are we going to make Toronto liveable?” Fox asked.

He said that cities should be smart in trying to do their best to provide us with the appropriate services, information and governance.

“But I believe we need to take a citizen perspective,” Fox said. “Not to replace a city perspective, but another perspective to add on to everything that we are doing.”

A citizen-centric perspective to the smart city vision puts the power in the hands of the people: they choose what services they want to use and participate in government by discovering the information and influencing municipal change.

“We just can’t leave it in the hands of the city to tell us how to do those things,” Fox said. “We have to do some of the heavy lifting.”

It is already happening: through smartphones, apps and cloud computing, citizens are taking control of their lives.

Fox said Uber, the popular mobile-app-based transportation network, is an example of the citizen-perspective approach to the smart city. The app informs the user where all of its taxis and rideshare vehicles are in relation to a user’s location.

He said the Uber of the future, ideally, would route and re-route individuals using various modes of travel—cars, bikes, private and public transportation—based on service availability and location.

Smart citizens need help, too

While citizens are gaining access to more information and the ability to control their urban environments, Fox questioned whether we actually have the capacity to manage it.

“We need something more to turn us into smart citizens,” he said. “We need something that’s going to help us deal with the volume of information flowing at us and the complex decisions we’re going to have to make. And that’s where intelligent agents and artificial intelligence comes in to play.”

Take Siri, Apple’s “personal assistant” for iOS mobile devices, which Fox referenced as a starting point for intelligent agents. At the core of Siri is artificial intelligence technology: speech recognition, domain or common-sense knowledge, planning capabilities—it’s all in there, in a device that fits inside of your pocket.

In the mid-1970s, Fox was a member of team that produced the first successful speech understanding system. The computer was huge—it filled a small room—had a vocabulary of about 100 words, performed a single task and was trained to recognize the speech of one person.

“We dreamed about this 40 years ago,” he said. “Today, it’s a reality.”

Originally published in the 2015 issue of Impact Magazine.

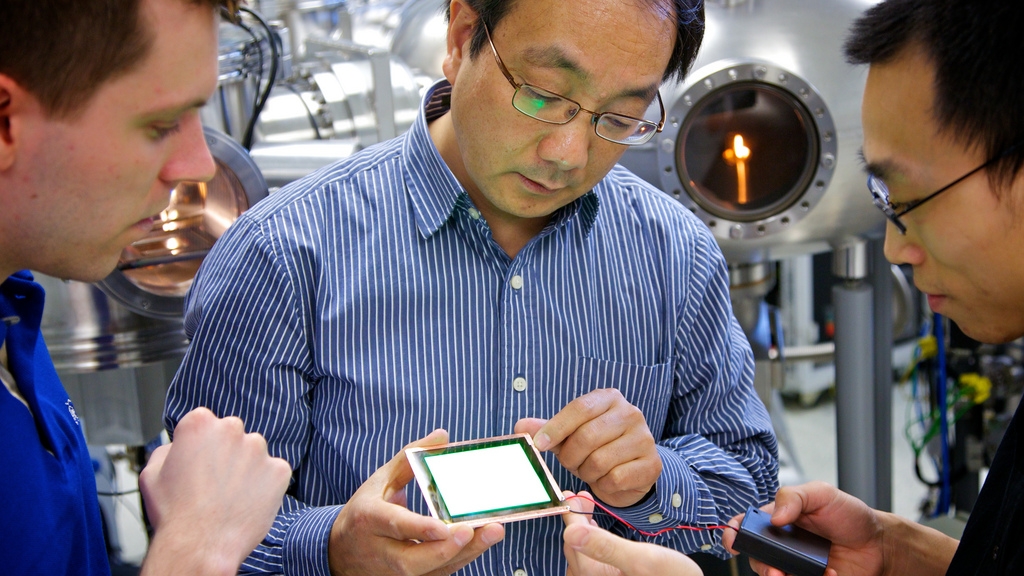

Google “OLED,” and you’ll find scores of articles confidently predicting that this is the year of the organic light-emitting diode. Some of those articles are ten years old. Still, there are reasons to believe the OLED age is finally dawning. In fact, engineering alumnus Michael Helander (EngSci 0T7, MSE PhD 1T2) is betting on it.

Three years ago, he was a PhD student with an important discovery just published in Science—a rising star who could have had his pick of academic postings. Instead, he gave up a life in research to start a technology company he named OTI Lumionics. The failure rate of technology startups, by some estimates, is 90 per cent.

Who would trade the life they’d dreamed of for a chance to play Russian roulette with five chambers loaded? Someone who’s counting on a lot more than just luck.

Why the fuss about OLEDs? And what on earth is an OLED? The best answer to both questions is OTI’s first and only consumer product, the aerelight. It’s an aluminum table lamp—sleek, angled, and a little retro (reminiscent of an older Canadian beauty, 1968’s Contempra phone). The light comes from a 10-cm square wafer no thicker than two sheets of paper—an OLED.

Not only is the lamp beautiful, so is its light. OLEDs are cool to the touch but warm to the eye, dimmable, flexible and efficient. They don’t blaze from a single spot like an LED; they diffuse evenly from every point on their surfaces, which can be arbitrarily large. After seeing the aerelight, other light sources—whether incandescent, fluorescent, or LED—immediately seem huge, hot and obsolete.

Like a conventional light-emitting diode, an organic LED produces light when a voltage is placed across it. The difference is the material between the electrodes. Instead of a crystalline semiconductor, OLEDs use organic compounds—plastics, in essence—similar to the pigments used in colour Xerox machines.

“LEDs are grown from perfect single crystals,” says Helander. “The probability of a defect increases exponentially with size, so it’s limited to a point source. Organic molecules don’t have any long-range order, so they don’t need a perfect single-crystal structure to work. That’s what allows you to distribute it across a large surface.”

Lighting isn’t the only place the OLED shines. It’s already made an appearance in smartphone displays and television screens, where its other advantages—richer colours, deeper blacks and near-instantaneous response times—make it the heir apparent to the liquid crystal display. But OTI is staying away from displays. Multinationals like Samsung and LG have already spent billions to enter and fight over that market.

Lighting, on the other hand, is still in its dark ages. Even the latest technology, the LED, comes packaged to resemble Thomas Edison’s 1880 bulb. That paradigm is about to shift. Soon, a light won’t be a product, but a feature of a surface—any surface. Windows, walls and wallpaper, furniture, cars, and clothes: light will come from everywhere.

If OTI succeeds, Toronto-born Michael Helander will be the reason. He’s a force of nature, intense, ambitious, and at 29, astonishingly accomplished.

As a kid, he wanted to be a scientist. Then he enrolled in the U of T’s Engineering Science program (“because people said it was the hardest”) and realized he wanted to be an engineer. While working on his PhD with Zheng-Hong Lu (MSE), professor and Canada Research Chair in Organic Optoelectronics in the Department of Materials Science & Engineering (“They had lots of shiny equipment, so that got me excited”), he realized he really wanted to be an entrepreneur.

He reached that decision after stumbling on a major discovery. Helander and OTI cofounder Zhibin Wang (MSE MASc 0T8, PhD 1T2) were working with indium tin oxide (ITO)—the industry-standard, transparent yet-conductive coating used in every kind of flat-panel display—when they noticed something unexpected. Some of their samples were working far more efficiently—carrying much more current—than they should. They assumed their equipment was improperly calibrated, but soon ruled that out. The effect was real. Their ITO had been contaminated.

It took months to find the culprit: chlorine from open bottles of cleaning fluid. “Basically, breaking the safety rules,” Helander quips. “The next step: how do we make use of it?”

Helander, Wang and Professor Lu published their answer in Science in May of 2011: chlorinated ITO. A one-atom thick layer of chlorine dramatically increased the brightness of OLEDs while reducing their energy consumption by up to 50 per cent. It also drastically lowered their cost by reducing the number of organic layers needed to make a diode from as many as eight to just two or three.

That news was greeted with considerable interest. “Big companies started approaching us,” Helander says. “They wanted to license or buy the technology. We thought, if they’re willing to pay this much now, there must be much more value than they’re letting on. Let’s try making a go of it ourselves.”

So they created OTI Lumionics. The initials don’t stand for anything. It’s just ITO backwards, a declaration that their approach would be 180 degrees from usual. “Lumionics” is a fabricated word that sounds like light, a choice Helander somewhat regrets because nobody seems able to spell it.

At first, Helander thought OTI would be nothing more than a stepping-stone to an academic career. “When we started the company, we viewed it as another checkbox on the academic CV. Successfully commercialized tech: check.”

But as the months rolled by, a desire to finish what they’d started in the lab took root. Helander and Wang decided their future lay with OTI. Giving up academia for entrepreneurship wasn’t hard, Helander said. By the time he’d earned his PhD, his name was on over a hundred publications, more than most researchers produce in an entire career.

“When you get up to that number of publications it’s almost like a paper mill; it’s just a formula you’re repeating,” he says. “It felt like we had learned the game and it wasn’t challenging anymore. We wanted new challenges.”

New challenges? Check.

Helander takes me into the back corner of OTI’s new offices in the University of Toronto’s venerable Banting Building on College Street. The room is dominated by a seven foot-tall vacuum-deposition chamber that looks like a giant robotic squid.

“This is our rapid prototyping module for organic LEDs,” he explains. “It allows us to make large, flexible panels in about an hour.” He bends a six-inch square sheet of shiny blue-green plastic—a freshly-made OLED—into a half-cylinder. I want to ask for details, but Helander is already talking about his plans for the larger, still empty, room adjacent.

“The pilot scale-up next door will be the same process, except it’ll be ten modules next to each other, so the production time goes down from an hour to minutes.”

Before I can quiz him on that, he’s shifted gears again. “The step after that, starting next year, is building a full production plant, hopefully somewhere in southern Ontario.” Helander speaks very fast, at the edge of comprehensibility, skipping syllables and sometimes entire words in a losing fight to keep up with his own thoughts. “We’ll be pulling together a whole syndicate of partners that are throwing in a whole bunch of support. We’re hoping to get money from the province as well and raise another round of financing. It’s a massive project.”

Sounds ambitious, I manage to interject. “Very ambitious,” he agrees. “People tell us we have lack of focus. But to understand our customers, we have to have our hands in everything. At the same time, we’re a small company. For what we’re doing we should have ten times the personnel and twenty times the capital. Trying to do the impossible—that’s how you succeed.”

It’s clear Helander’s ambition doesn’t stop at table lamps. In fact, it doesn’t even include table lamps—or didn’t, until he and OTI’s senior product designer, Ray Kwa (EngSci 0T0 + PEY), built a few prototypes. Everyone who saw them had the same three questions: “When can I buy it? When can I buy it? When can I buy it?”

So OTI’s nine employees are making OLED panels and assembling lamps on College Street. At the same time, multibillion-dollar giants like Philips, LG and Konica Minolta are preparing to turn out OLED panels by the million. In a few months, OLED table lamps may be going for a fraction of the price—$239 (USD)—of an aerelight.

Remarkably, Helander is unfazed by that prospect. “That would make us so happy,” he says. “It would prove that we’re on the right track and the market is there.”

Helander’s plan is not to sell lamps but to service niches—lots and lots of niches—that are too small for the giants. “There are a lot of partners we work with who only want 10, 50, 100, units. A massive production line can’t do that effectively. Our vision is to enable hundreds of companies, delivering on-demand whatever people need, for applications in lighting, furniture, automotive, wearables, whatever you want.”

Like any entrepreneur, Michael Helander sounds more confident than he has any right to be. For the foreseeable future, OTI will live amongst threats: an untested market, ever-mutating technology, giants ready to grind him to paste, uncertain financial backing. To defend himself, Helander has little more than a small pool of talents, patents and ambitions.

Of course, in his case, that might just be enough.

Impact Magazine is an annual publication from University of Toronto Department of Materials Science & Engineering.

Impact Magazine is an annual publication from University of Toronto Department of Materials Science & Engineering.