For an upcoming episode of Spark, host Nora Young spoke to Professor Andrew Goldenberg (MIE), who spearheads the Robotics and Automation Lab at the University of Toronto, on why researchers are obsessed with replicating robots to the human form.

To hear the full interview, visit the CBC website.

Vivian Hui, a third-year University of Toronto Engineering Science student from Markham, Ontario, has won the 2011 Canadian Engineering Memorial Foundation (CEMF) Undergraduate Scholarship – Ontario Region in a strong field of competitors.

Hui will join four other undergraduate engineering students, from the regions of British Columbia, Prairies, Quebec and Atlantic, as the newest ambassadors and role models for women in engineering across Canada in 2011.

The CEMF awards five $5,000 scholarships annually to the most promising women in an accredited undergraduate engineering program in Canada. The award recognizes leadership and extracurricular activities. All the recipients are actively involved in their communities, volunteer many hours to helping others and are strong role models for the engineering profession. Competition was fierce this year, with many outstanding applicants.

Hui – who is enrolled in Engineering Science with a chosen major in infrastructure – is a co-chair of the U of T club Eyes of Hope. The club fundraises for charities such as World Vision Canada, Free the Children and Habitat for Humanity, for which it has so far raised over $30,000 to build a home. It also engages in projects such as the Umbrella Painting Initiative, which engages homeless youth in creative activity during weekly suppertime drop-ins at Toronto’s Knox Presbyterian Church.

“Vivian is a devoted volunteer, exceptional future engineer and ambassador for the profession who is richly deserving of this prestigious scholarship,” said Cristina Amon, Dean, Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering. “I am delighted that she is being recognized by the CEMF for her many leadership contributions to the community.”

The winners “are joining the ranks of over 100 other remarkable women who have received a CEMF scholarship, and who, collectively, represent the very best the engineering profession has to offer,” said Huntley O’Connor, P.Eng., CEMF President. “We are confident each will go on to successful careers as professional engineers.”

The awards will be presented at the CEMF annual awards luncheon being held in Halifax next month.

Since 1990, the Canadian Engineering Memorial Foundation has promoted engineering as a career choice for young Canadian women through its extensive scholarship program, a website that attracts thousands of new visitors a month, social media programming, and via the scholarship winner presentations to high-school students.

Chlorine is an abundant and readily available halogen gas commonly associated with the sanitation of swimming pools and drinking water. Could a one-atom thick sheet of this element revolutionize the next generation of flat-panel displays and lighting technology?

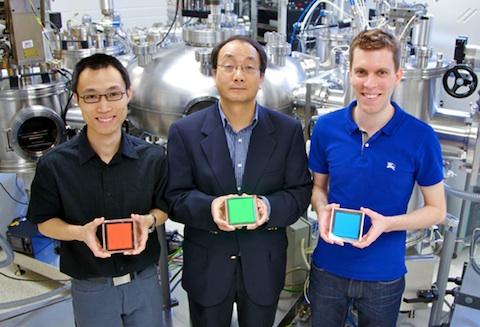

In the case of Organic Light-Emitting Diode (OLED) devices, it most certainly can. Primary researchers Michael G. Helander (PhD Candidate and Vanier Canada Graduate Scholar), Zhibin Wang (PhD Candidate), and led by Professor Zheng-Hong Lu of the Department of Materials Science & Engineering at the University of Toronto, have found a simple method of using chlorine to drastically reduce traditional OLED device complexity and dramatically improve its efficiency all at the same time. By engineering a one-atom thick sheet of chlorine onto the surface of an existing industry-standard electrode material (indium tin oxide, ITO) found in today’s flat-panel displays, these researchers have created a medium that allows for efficient electrical transport while eliminating the need for several costly layers found in traditional OLED devices.

“It turns out that it’s remarkably easy to engineer this one-atom thick layer of chlorine onto the surface of ITO,” says Helander. “We developed a UV light assisted process to achieve chlorination, which negates the need for chlorine gas, making the entire procedure safe and reliable.”

The team tested their green-emitting “Cl-OLED” against a conventional OLED and found that the efficiency was more than doubled at very high brightness. “OLEDs are known for their high-efficiency,” says Helander. “However, the challenge in conventional OLEDs is that as you increase the brightness, the efficiency drops off rapidly.”

Using their chlorinated ITO, this team of advanced materials researchers found that they were able to prevent this drop off and achieve a record efficiency of 50% at 10,000 cd/m2 (a standard florescent light has a brightness of approximately 8,000 cd/m2), which is at least two times more efficient than the conventional OLED.

“Our Cl-ITO eliminates the need for several stacked layers found in traditional OLEDs, reducing the number of manufacturing steps and equipment, which ultimately cuts down on the costs associated with setting up a production line,” says Professor Zheng-Hong Lu.

“This effectively lowers barriers for mass production and thereby accelerates the adoption of OLED devices into mainstream flat-panel displays and other lighting technologies.”

The results of this work were published online today in the journal Science.

Read more at Engadget , Ubergizmo , The Engineer and Printed Electronics World .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rc7p7J3dOjE

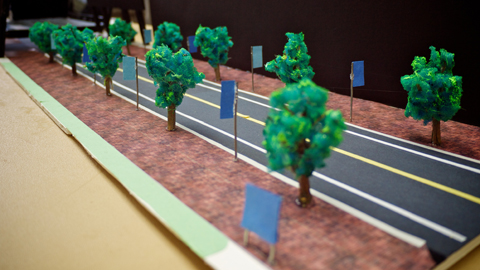

Tasked with the challenge to design for Toronto, first-year EngSci Praxis II students stepped up to the plate and came up with creative, sustainable and feasible innovations to enhance the city’s infrastructure.

At the 2011 Praxis II Showcase, held at the Bahen Centre for Information Technology, on April 12, students’ designs tackled everything from retrofitting litter bins, to building roads to connect the city with the waterfront, to improving track lubrication at the Union Station subway loop.

Kevin Shu’s (EngSci 1T4) group was one of several who tackled the latter. His group presented an automated robotic system that helps the TTC efficiently monitor and lubricate the tracks at Union Station – a viable solution that would give many commuters’ ears some much-needed relief when travelling past the Union loop.

“It’s been very overwhelming,” said Shu about the showcase, “But we’re so proud to share what we came up with.”

“It’s been nice to see the five-year evolution of the course,” said Senior Lecturer Jason Foster (EngSci). “We are continuously trying to figure out the right scale of which to have the students look at the city – do we restrict it to the TTC, or can they only look at certain regions? This year, we said, ‘sustainably improve the city of Toronto,’ and that was the end of it. So students came back with everything from TTC issues, to cycling, to improving the waterfront to vermin and pest control, to homelessness.”

Before they could present their completed designs to fellow students, faculty members and media at the showcase, Praxis students had to communicate and engage with community members and civic agencies in order to conceptualize their designs – which is one of many elements that makes Praxis so unique, said Foster.

“It’s not strictly a design and communication course, because those are just the activities we ask the students to pursue, with the bigger goal that it’ll let them figure out, ‘what kind of engineer do I want to be?’”

Read the articles on the Praxis II showcase as they appeared in The Globe and Mail, National Post, Toronto Star and the Daily Commercial News .

Around the world, there are millions who cannot speak, either because of brain injuries or conditions such as autism. Now, some students at the University of Toronto have come up with an app that merges a voice synthesizer with a GPS to give people the words they need, wherever they are.

The device is called MyVoice. It’s an assistive communication device similar to the technology used by Stephen Hawking that helps users to speak. But unlike the unwieldy and expensive voice synthesizers of old, MyVoice can be downloaded onto iPhones, iPads and Android devices.

The app helps users create customized dictionaries of their most commonly used words and phrases to fit their most common conversation topics.

What makes MyVoice unique is that it’s location-specific, built to use a smartphone’s GPS system to determine the user’s location. It then pulls up the phrases they need for that location.

“So when you go to Tim Hortons, you get words like ‘Timbits’ and ‘double-double.’ When you go to the movie theatre, you get ‘tickets,’ ‘seats’, ‘soft drinks’,” explains designer Aakash Sahney (EngSci, ECE option).

“Usually, people would have to navigate through a huge hierarchy of words on a traditional device in order to find these seemingly unrelated words. But using our technology, using MyVoice, they’re able to very quickly get to the words that they actually need to say at that time.”

The Academic Policy and Programs Committee of Governing Council approved a new Engineering minor program in Robotics and Mechatronics on Tuesday.

The new minor will be launched in the upcoming 2011-2012 academic year, and will allow students to explore fundamental enabling technologies that render robotic and mechatronic systems into viable consumer products. Coursework will cover micro-electromechanical systems and nanotechnology, advanced techniques for signal processing and systems control, and new system-level principles underlying embedded systems.

Following the creation of the Institute for Robotics and Mechatronics (IRM) in 2010, the minor is a collaborative effort between The Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, the Department of Mechanical & Industrial Engineering, the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies, and the Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineering.

“We have a lot of strength in the Faculty in mechatronics and robotics,” said Professor Ridha Ben Mrad (MIE), Director of IRM and one of the chief proponents of the new minor. “This minor program will provide our students with the ability to pursue a structured program that provides in-depth studies in this area and takes advantage of extensive teaching facilities and resources from across the Faculty.”

Consistent with other Engineering minor program requirements, students will take six semester-long courses – two required courses plus four electives – from a selection of robotics and mechatronics-designated courses. These offerings will include Microprocessors Applications (MIE) and Mechatronics Principles (MIE), a capstone design course, said Professor Ben Mrad.

“There’s a lot of interest in this area,” he added. “I think it will be very popular with students. It is definitely a growing area [and] will enhance the student experience.”

This minor will join the four current distinctive offerings of the Cross-Disciplinary Programs office, which offers a full slate of Engineering minor and certificate programs.