The University of Toronto is home to a new “self-driving lab” that will allow researchers to better understand health and disease — and to more rapidly test the efficacy and toxicity of new drugs and materials.

Based at the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, the Self-Driving Laboratory for Human Organ Mimicry is the latest self-driving lab to spring from a historic $200-million grant from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund to the Acceleration Consortium — a global effort to speed the discovery of materials and molecules that is one of several U of T institutional strategic initiatives.

The new lab will be led by Professor Milica Radisic (ChemE, BME, Donnelly Centre), Canada Research Chair in Organ-on-a-Chip Engineering, and Vuk Stambolic, senior scientist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, and a professor of medical biophysics in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

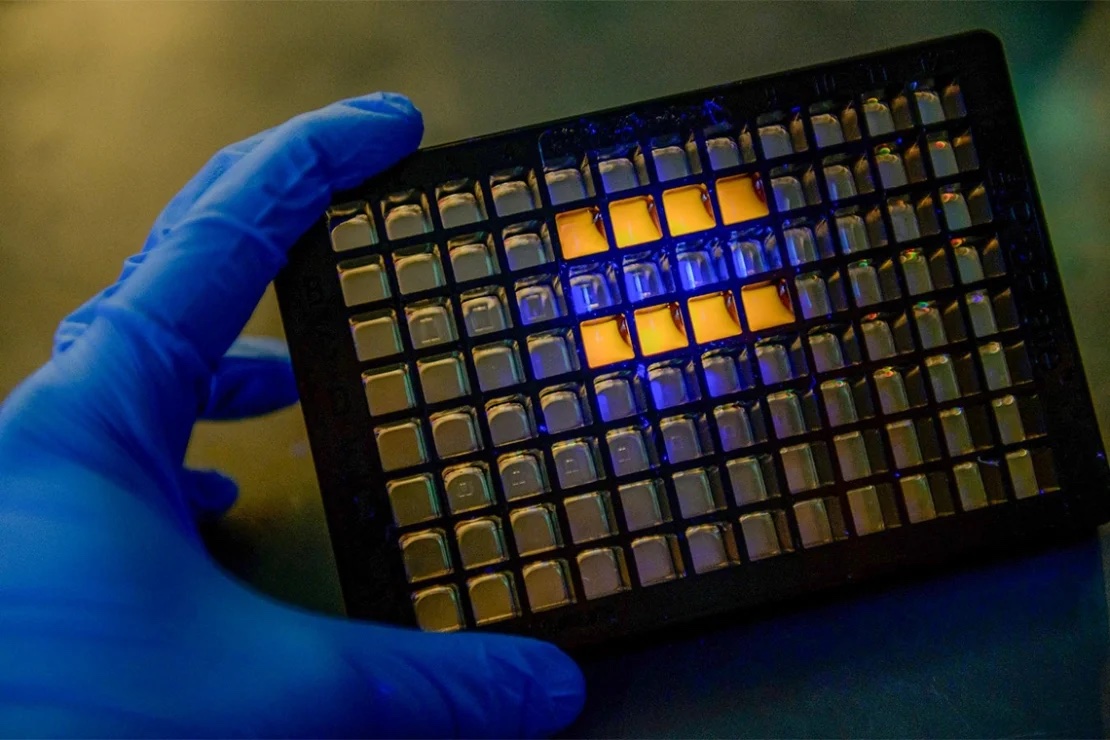

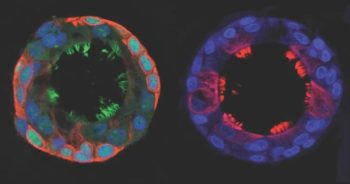

“The lab will innovate new complex cellular models of human tissues, such as from the heart, liver, kidney and brain, through stem-cell-derived organoids and organ-on-a-chip technologies,” says Radisic. “In partnership with the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, the lab will also enable automation of patient-derived tumour organoid cultures to accelerate the discovery of new cancer treatments.”

The Self-Driving Laboratory for Human Organ Mimicry is one of six self-driving labs launched by the Acceleration Consortium at U of T to drive research across a range of fields, including materials, drug formulation, drug discovery and sustainable energy.

How does a self-driving lab work? Once set up, it runs with robots and artificial intelligence performing as much as 90% of the work. That, in turn, speeds up the process of discovery by freeing researchers from the tedious process of trial and error so they can focus on higher-level analysis.

“The Self-Driving Lab for Human Organ Mimicry will enable other self-driving labs to develop new materials and drugs by rapidly determining their efficacy, as well as their potential toxic effects and other impacts on human tissues,” says Stambolic. “While animal testing is typically the go-to method to assess the safety of new molecules made for humans, this lab will replace trials involving animals with organoids and organs-on-chips. This will allow us to advance to human clinical trials much more quickly.”

“The goal of our self-driving labs is to use AI to move the discovery process forward at the necessary pace to tackle global issues,” says Alán Aspuru-Guzik, director of the Acceleration Consortium and a professor of chemistry and computer science in the Faculty of Arts & Science. “The Human Organ Mimicry SDL, as well as other self-driving labs launched through the Acceleration Consortium, will establish U of T and our extended research community as a global leader in AI for science.”

Donnelly Centre Director Stephane Angers says the centre is an ideal environment for the new lab, citing the international hub for cross-disciplinary health and medical research’s reputation as a hotspot for technological innovation — one that offers resources to the wider research community.

“The Donnelly Centre is a thriving research community because it was founded on the principle of interdisciplinary collaboration,” says Angers, a professor of biochemistry and pharmaceutical sciences. “Our research strengths in computational biology, functional genomics and stem cell biology will catalyze the development and success of the Self-Driving Lab for Human Organ Mimicry.”

The launch of the new lab will also expand the Donnelly Centre’s team of experts with the hiring of five new staff who will work to make the self-driving lab fully automated. The lab is expected to be operational by the end of the year.