A U of T Engineering team has collaborated with researchers in the Wilfred and Joyce Posluns Centre for Image Guided Innovation and Therapeutic Intervention at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) to create a set of tiny robotic tools that could enable ‘keyhole surgery’ in the brain.

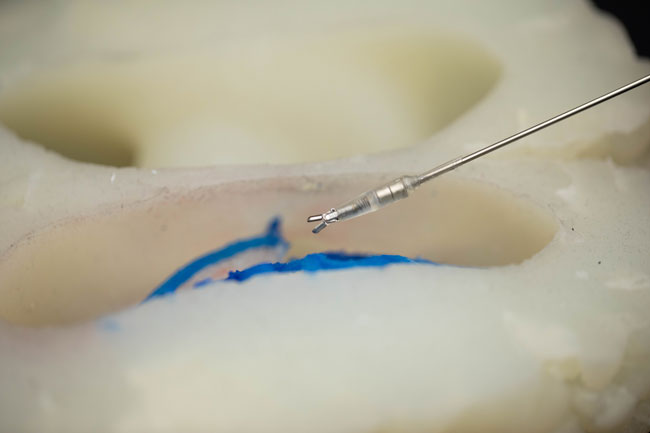

In a paper published in Science Robotics, the team demonstrated the ability of these tools — only about 3 millimetres in diameter — to grip, pull and cut tissue.

Their extremely small size is made possible by the fact that they are powered not by motors but by external magnetic fields.

“In the past couple of decades, there has been this huge explosion of robotic tools that enable minimally invasive surgery, which can improve recovery times and outcomes for patients,” says Professor Eric Diller (MIE).

“We can now replicate the wrist and hand movements of a surgeon on a centimetre scale, and these tools are widely used in surgeries that take place in the torso. But when it comes to neurosurgery, we are working with an even more restrictive space.”

Current robotic surgical tools are typically driven by cables connected to electric motors, in much the same way that human fingers are manipulated by tendons in the hand that are connected to muscles in the wrist.

But Diller says that at smaller length scales, the cable-based approach starts to break down.

“The smaller you get, the harder you have to pull on the cables,” he says. “And at a certain point, you start to get problems with friction that lead to less reliable operation.”

Diller and his collaborators have been working for several years on an alternative approach. Instead of cables and pulleys, their robotic tools contain magnetically active materials that respond to external electromagnetic fields controlled by the surgical team.

The system consists of two parts. The first is the tiny tools themselves: a gripper, a scalpel and a set of forceps. The second part is what the team calls a coil table, which is a surgical table with several electromagnetic coils embedded inside.

In this design, the patient would be positioned with their head on top of the embedded coils, and the robotic tools would be inserted into the brain by means of a small incision.

By altering the amount of electricity flowing into the coils, the team can manipulate the magnetic fields, causing the tools to grip, pull or cut tissue as desired.

To test the tools, Diller and his team partnered with physicians and researchers at SickKids, including Doctors James Drake and Thomas Looi (EngSci 0T0). Together, they designed and built a phantom brain — a life-sized model made of silicone rubber that simulates the geometry of a real brain.

The team then used small pieces of tofu and bits of raspberries to simulate the mechanical properties of the brain tissue they would need to work with.

“The tofu is best for simulating cuts with the scalpel, because it has a consistency very similar to that of the corpus collosum, which is the part of the brain we were targeting,” says Changyan He, a former postdoctoral fellow co-supervised by both Drake and Diller, now an assistant professor at the University of Newcastle in New South Wales, Australia.

“The raspberries were used for the gripping tasks, to see if we could remove them in the way that a surgeon would remove diseased tissue.”

The performance of these magnetically-actuated tools was compared with that of standard tools handled by trained physicians.

In the paper, the team reports that the cuts made with the magnetic scalpel were consistent and narrow, with an average width of 0.3 to 0.4 millimetres.

That was even more precise than those from the traditional hand tools, which ranged from 0.6 to 2.1 millimetres.

As for the grippers, they were able to successfully pick up the target 76% of the time.

The team also tested the operation of the tools in animal models, where they found that they performed similarly well.

“I think we were all a bit surprised at just how well they performed,” says He.

“Our previous work was in very controlled environments, so we thought it might take a year or more of experimentation to get them to the point where they were comparable to human-operated tools.”

Despite the team’s success so far, Diller cautions that it may still be a long time before these tools see the inside of an operating room.

“The technology development timeline for medical devices — especially surgical robots — can be years to decades,” he says.

“There’s a lot we still need to figure out. We want to make sure we can fit our field generation system comfortably into the operating room, and make it compatible with imaging systems like fluoroscopy, which makes use of X-rays.”

Still, the team is excited about the potential of the technology.

“This really is a wild idea,” says Diller.

“It’s a radically different approach to how to how to make and drive these kinds of tools, but it’s also one that can lead to capabilities that are far beyond what we can do today.”

Estelle Oliva-Fisher, Managing Director of the Troost Institute for Leadership Education in Engineering, is one of three recipients of the University of Toronto’s 2025 Chancellor’s Emerging Leader Award.

Part of U of T’s Pinnacle Awards Program, this honour recognizes an individual who demonstrates outstanding leadership and significantly advances the University’s mission to foster an academic community in which the learning and scholarship of every member may flourish.

Oliva-Fisher first joined the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering in 2010 as a Leadership Education Specialist with the Troost Institute for Leadership Education in Engineering, providing support for student and staff learning and development. Currently, she serves within the Institute for Studies in Transdisciplinary Engineering Education and Practice (ISTEP), where she leads and develops student co-curricular initiatives and industry partnerships.

During her time at the faculty, Oliva-Fisher has led multiple innovative initiatives, identifying and addressing gaps, developing impactful strategies, and then implementing plans to ensure the solutions continue beyond her immediate oversight.

Some of her notable accomplishments include the creation of the Engagement & Development Network for U of T Engineering staff, her leadership of the Decanal Task Force on Mental Health and implementation of its recommendations, the development of the Professional Experience Year Co-op Preparatory Program, and being an original member of the team that expanded the Leaders of Tomorrow program faculty wide,

“Estelle consistently builds strong partnerships with her colleagues, students and alumni across U of T Engineering, creating an inclusive environment where all can thrive,” says Professor Greg Evans, Director of ISTEP.

“Her investment in the success of our faculty across so many initiatives has been a tremendous benefit to our students’ experience, and we are thrilled that her leadership has been recognized with this award.”

A new study from U of T Engineering researchers points to practical strategies to prevent deaths from opioid poisoning by optimizing the distribution of naloxone kits.

In a paper published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, Professor Timothy Chan (MIE) and his team showed that placing naloxone kits in transit stations could help ensure that these potentially life-saving tools are present where they are most needed.

“The opioid epidemic is a profound public health crisis, and it may not be obvious at first how engineering researchers can help,” says Chan.

“In collaboration with doctors and other medical professionals, we can apply techniques from our field — operations research and mathematical optimization — to develop new solutions.”

Chan and his team have previously collaborated with medical researchers to look at the distribution of automated external defibrillators, or AEDs, in urban areas.

Using computer models, they were able to analyze spatial data on past cardiac arrests. They could then optimize AED placement to maximize the number that would be accessible from those locations.

“Naloxone kits are somewhat analogous to AEDs in that they can reverse the effects of an opioid poisoning event, but only if they are available quickly, which means they need to be in the right locations,” says Chan.

In their latest work, Chan and his team collaborated with emergency physicians and researchers, including Dr. Brian Grunau and Dr. Jim Christenson at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, B.C.

They began by analyzing data from more than 14,000 opioid poisoning incidents that were recorded by BC Emergency Health Services between December 2014 and August 2020 in Metro Vancouver.

They then built a computer model that could simulate how many of those incidents would have taken place within a 3-minute walk from a naloxone kit, based on several distribution strategies.

“The first strategy was to look at locations that already have free naloxone distribution programs, such as pharmacies and health clinics,” says Ben Leung (IndE 1T6 + PEY, MIE MASc 1T9, PhD 2T4), lead author on the paper.

Leung built the model while working as a PhD student in Chan’s lab; he is now a research fellow at the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

“Our second strategy was to look at chain restaurants or similar businesses. And our third strategy was to look at transit, including both SkyTrain stations and bus stops.”

Leung’s analysis showed that more than a third of past opioid poisonings took place within about 150 metres of locations where naloxone is being distributed.

Switching to a strategy focusing on chain restaurants and similar businesses did not noticeably improve coverage: depending on how many different chains were included and how many kits distributed, coverage only reached a maximum of about 20%.

But the third strategy of leveraging transit stops was the most promising.

“Right now, there are about 650 locations with take-home naloxone distribution programs,” says Leung.

“What we found was that if we used transit stops instead, we could get the same amount of coverage with only about 60 kits. If we increase the number of kits to 1000, we could cover more than half of the opioid poisonings that we analyzed.”

Leung points out that different strategies can be used in combination to further improve coverage. He hopes that the insights that have been generated by the new study will help public health officials make better strategic decisions in the future.

“There have been a few small pilot programs putting naloxone kits in public locations, but to our knowledge, this is the first time anyone has analyzed what large-scale distribution would look like using mathematical optimization techniques,” he says.

“By presenting these results, I think we can make a strong case for doing that.”

Chan hopes that these kinds of studies can seed broader changes as well.

“For example, in Japan, AEDs are widely available at vending machines,” he says.

“That has led to an association: if someone is having a cardiac arrest, you automatically know to go to the nearest vending machine for an AED.

“If we can do something similar for naloxone, it could help bystanders feel more empowered to step in when they are needed to save lives.”

The University of Toronto and Konica Minolta, Inc. — the Japanese digital print, imaging and information technology company — are renewing a research partnership focused on artificial intelligence and internet-connected devices, which are sometimes referred to as the Internet of Things (IoT).

The partnership, first launched in 2020, was officially extended for another five years during a recent event at U of T’s Myhal Centre for Engineering Innovation & Entrepreneurship on the St. George campus.

The collaboration thus far has involved projects with three research groups, including information engineering researchers from U of T’s Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, computer systems researchers from the department of computer science in the Faculty of Arts & Science and robotics researchers from U of T Mississauga.

“We are happy to celebrate the fact that Konica Minolta is extending its partnership with U of T until at least 2030, and we are confident that it will continue for many years beyond that,” says David Wolfe, U of T’s acting associate vice-president of international partnerships.

“We also recognize that you are doing so because there is nowhere else in the world where you can conduct research with expertise at scale like you can at U of T.”

The partnership renewal follows a visit by Konica Minolta representatives to U of T last year. In addition to reviewing their existing collaborations, the Tokyo-headquartered company was keen to learn more about the Acceleration Consortium, a U of T institutional strategic initiative that is using artificial intelligence and self-driving labs to speed the discovery of critical new materials.

“We are pleased to extend our partnership with University of Toronto, which started in 2020 as an AI, IoT technology research collaboration,” says Toshiya Eguchi, Konica Minolta’s executive vice-president and executive officer who is responsible for technologies.

“I’m hopeful that our partnership over the next five years will produce exciting results.”

Eldan Cohen, an associate professor in U of T’s Department of Mechanical & Industrial Engineering in the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, is one of the researchers that has been involved with the partnership since its inception. Along with his research team, Cohen is working with Konica Minolta to improve manufacturing processes using an explainable machine learning model and IoT technologies.

“The main goal is to make those factories more efficient,” says Cohen. “The idea is to try to … predict that we’re going to have an issue [so] they can quickly try to intervene and solve the issue — and also to help them figure out where the issue is coming from.”

He added that the partnership has been extremely beneficial for his students.

“It’s usually very difficult to get access to real data, but by working on this project we were able to understand the real problems that factories are facing and develop a solution that would actually be useful.”

Ultimately, Cohen says he hopes state-of the-art AI solutions developed by the collaborative project can be adopted by other manufacturers, as they not only help improve the efficiency of manufacturing plants but also help reduce waste.

“What you want to do is make sure products are coming out without any flaws.”

Similarly, Konica Minolta says the research that flows out of the partnership will help it to reduce its environmental footprint.

“By extending our partnership with University of Toronto — which is bringing advanced AI technologies to the field of material design, development and manufacturing — we will be able to reduce environmental impact and further strengthen our contribution to society,” says Eguchi.

Distinguished alumnus and donor Paul Cadario (CivE 7T3, Hon LLD 1T3) has had a significant impact on the lives of thousands of students.

His passion for education and community development is reflected through his generous contributions to student scholarships and university infrastructure. His transformational gifts include establishing the Paul Cadario Chair in Global Engineering, the Paul Cadario Civil Engineering Award, and the Experiential Learning Student Awards and Social Impact Internships in both the Faculty of Arts & Science and the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering.

For U of T Giving Day — a 24-hour fundraising campaign on March 25 — writer Kristina Kazandjian spoke with Cadario about his journey from civil engineering to the World Bank, the impact of scholarships on his education, and the importance of giving back.

What are your thoughts on engineering as a profession that can lead you anywhere?

Engineers are trained to see systems and operate within complex environments. These skills are invaluable in a wide range of fields that engineers take up with great success, from technology to law to business.

For example, my own field, global development and poverty eradication, involves intricate economic, financial and political systems that evolve rapidly and sometimes unpredictably.

The adaptability that an engineering education provides makes it a great way to open doors to countless opportunities.

What was the first donation you made to U of T and what was the inspiration behind the gift?

The first donation I remember was to support a modest scholarship; as a young World Bank staffer with a mortgage, it was all I could scrape together at the time. But it felt important to do so. It was my way of saying thank you for the U of T entrance scholarship, and for the Inco scholarship that covered my tuition.

This financial aid meant that my mother, who was widowed young, didn’t have to worry about supporting me through university. The scholarships I received meant I could work summer jobs related to engineering, gaining practical skills before graduation. Measuring water currents and temperatures at future Ontario Hydro generating sites and examining municipal services in Inuit communities in Nunavut gave me real-world insights into how engineering impacts communities.

You chose a somewhat unconventional career path after engineering: the World Bank. How did your time there shape your approach to philanthropy and giving back?

It’s fair to say that graduating from civil engineering, specialized in urban transport and the environment made me close to being a social scientist and comfortable with quantitative economics and data analysis. This skill set was invaluable when I joined the World Bank, which still hired many engineers due to its origins in reconstruction and development.

For example, my training helped me explain to colleagues why groundwater irrigation on the Greek side of a river would impact groundwater on the Turkish side as well, and the political problems that might raise. Another example: an architect colleague and I concluded that a government’s interest in an urban freeway had more to do with who owned the property than it did with inflated traffic counts. The hours I’d spent counting cars turning from McCaul onto College Street during Traffic Engineering and analyzing the number of homes the Scarborough Expressway would cut through taught me to consider the broader impact of investments on real people.

Ultimately, philanthropy is about making a tangible difference in people’s lives, whether through better classrooms and labs for students or ensuring that the brightest minds have access to education regardless of their financial means.

You’ve made significant contributions to the University of Toronto, mostly to student awards. What motivates your generosity toward the university and why is student access so important?

I owe my education to the generosity of others, having attended U of T and Oxford on scholarships. Giving back is my way of paying it forward and ensuring that talented students can attend U of T regardless of their financial situation.

On top of that, my volunteer work since graduating has given me a deep understanding of all the incredible teaching and research happening at U of T. I want to support, maintain and expand that excellence.

How do you see your philanthropic efforts benefiting the next generation of students and the broader community?

Our future depends on having great scholars and teachers advancing knowledge. I’m thrilled with the impact the Centre for Global Engineering has had, from bringing water innovation to poor communities to advancing rapid diagnostics for health centres.

Graduates from U of T Engineering and the Munk School have gone on to influential roles in government, consulting, banking and other sectors, reflecting well on U of T’s academic community. Investments in facilities for the Department of Civil & Mineral Engineering and University College create spaces for learning and discussion. Bringing people together in this way is what great research universities do.

Can you share a story or moment that made you especially proud of your involvement with the university?

There are many moments, but celebrating Geoff Hinton’s Nobel Prize in Stockholm stands out.

His work on artificial intelligence has had a profound impact on science and our daily lives, highlighting the importance of addressing the ethical and societal implications of technological advancements. It’s moments like these that make me proud to support U of T.

For someone interested in giving back but unsure where to start, what would you recommend as the first step?

Volunteer. Learn about what’s happening at U of T in a field that excites you and talk to a favourite professor about how you can get involved.

Engage with your community and share how U of T and other post-secondary institutions contribute to society. Encourage young people to consider U of T for their education and future careers.

On March 13, U of T Engineering students were celebrated for their leadership and service to the university at an event hosted by the U of T Engineering Office of Advancement, the Engineering Society (EngSoc), and the offices of the Vice-Dean Undergraduate and the Vice-Dean Graduate.

At the celebration, 16 students were presented with the University of Toronto Student Leadership Awards (UTSLA), recognizing their contributions to student clubs and design teams, fostering inclusivity through outreach activities and events, and advocating for students by strengthening support systems for academic success, mental health and sexual violence prevention.

The UTSLA was established in 1994 by the University of Toronto Alumni Association in honour of Gordon Cressy, former vice-president, development and university relations to celebrate students whose service has had a lasting impact on their peers and the university.

Also at the event, members of EngSoc and the Graduate Engineering Council of Students (GECoS) celebrated their outgoing student leaders, and recognized the contributions made to student life with the EngSoc Awards.

“Our student leaders work tirelessly each year to make our community a better place for everyone. Their contributions inspire their peers, as well as future students, and make this faculty such a wonderful place,” says Chris Yip, Dean of U of T Engineering.

“I look forward to seeing what each of them will accomplish as our future engineering leaders. Congratulations to all our U of T Engineering student leaders.”

The UTSLA recipients for 2025 are:

- Abeer Fatima

- Armita Khashayardoost

- Ashna Jain

- Badr Abbas

- Cassidy Tan

- Dina Aynalem

- Janishan Jeyarajah

- Madeline Kalda

- Prarthona Paul Priya Jadav

- Seung Jae Yang

- Sophie Sun

- Tobin Zheng

- Vivek Vinay Dhande

- Wanda Janaeska

- Zijie (Jason) Zhou

Outgoing EngSoc Leadership

- Inho Kim, President

- Zayneb Hussain, Vice-President of Finance

- Jennifer Wu, Vice-President of Communications

- Katherine Jia, Vice-President of Academics

- Sean Huang, Vice-President of Student Life

Outgoing GECoS Leadership

- Tess Seip, President

- Brohath Amrithraj, Vice President of Finance

- Melody Li, Vice President of Communications

- Sharini Sam Chee, Vice President of Student Life

- Aryan Singh, Vice President of Professional Development

EngSoc Award Winners

- Engineering Society Centennial Award: Justin Fang and Christopher Lee

- Engineering Society Semi-Centennial Award: Lauren Altomare and Kai Hashimoto

- Engineering Society Award: Sean Huang

- Skule™ Cannon Award: Ashna Jain

- Discipline Club of the Year: Mechanical Engineering Club

- Affiliated Club of the Year: University of Toronto Nuclear Energy Association

- Director of the Year: Tait Berlette and Zijie (Jason) Zhou

- Representative of the Year: Kelvin Lo and Sebastian Kiernan

- Joe Club Award: Badr Abbas

- L.E. Jones Award for Arts in Engineering: Reid Sox-Harris

See more photos from the event in our Flickr gallery.