How do you design an inexpensive stove that’s better than open fires or rudimentary appliances, and then convince people halfway across the world to use it?

That’s what a multidisciplinary team of students and professors from across the University of Toronto – including U of T Engineering – went to South India to discover.

“According to the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, nearly three billion people are using solid fuels for cooking,” said the team’s lead, Mimi Liu, an undergraduate student in economics and peace, conflict and justice.

“Exposure to smoke from traditional cooking practices causes four million premature deaths per year,” she said, “and women and children are the most affected. Household fuel combustion also contributes to climate change, [and] poor households often spend a significant portion of their income on cooking fuel.”

Prakti Design, an award-winning social enterprise based in South India, is trying to do something about these issues. They’ve developed a line of household and institutional clean cookstoves that use biomass fuels from wood, charcoal and briquettes that lessen fuel consumption by up to 80 per cent, potentially eliminate air pollution and cut down cooking times by up to 70 per cent — compared to traditional three-stone fires.

“Reducing emissions in the home can improve respiratory health outcomes, especially for young children,” said Hayden Rodenkirchen, an international relations student who participated in the trip. “For families or institutions that have to buy wood, the fuel efficiency of these stoves can save them money over time. For those who have to gather wood, the fuel efficiency means fewer trips into the woods and lighter loads to carry.”

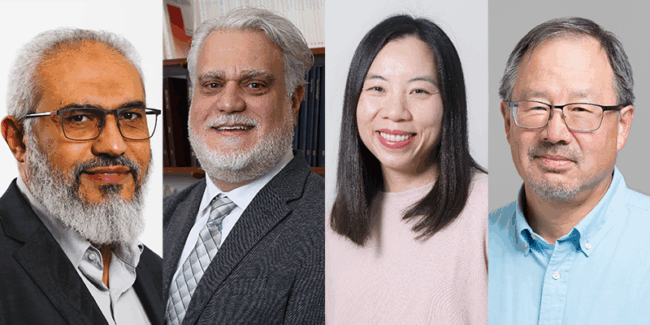

Prakti invited U of T’s Global Innovation Group — a network of professors interested in poverty and innovation in developing countries — to help research and address challenges related to clean cookstove technology, distribution and adoption. The team included: Yu-Ling Cheng, a chemical engineering professor and director of the Centre for Global Engineering; political science professor Joseph Wong, Canada Research Chair in Health and Development; Stanley Zlotkin, a nutritional sciences and pediatrics professor; and, Poornima Vinoo, a research associate at the Rotman School of Management.

Liu brought together a student research team for the trip, including chemical engineering student Tameka Deare (ChemE 1T3 + PEY), as well as Kay Dyson Tam of psychology and peace, conflict and justice, Seemi Qaiser of global health studies and Hayden Rodenkirchen.

For months before the trip to India, the student team gathered secondary research, conducted phone interviews, wrote briefings and made presentations on clean cookstove technologies, distribution models, adoption patterns and impacts.

The group then travelled to South India for approximately one week in March 2014, visiting Chennai, Puducherry and Auroville to conduct interviews with diverse stakeholders, such as users, designers, manufacturers, distributors, funders and researchers.

One memorable series of interviews involved speaking with women in their homes in villages near Puducherry. One of the students asked about the women’s experiences with wood collection, a task that occupies many women in rural areas of India for many hours a week.

“They all erupted and started shouting,” said Rodenkirchen. “All that our translator could say was ‘they really, really hate it!’”

“Women also recommended larger openings in the stoves, so they wouldn’t have to chop wood into such small pieces,” said Liu. “Clean cookstoves need to be iteratively designed with more input from end-users and sustained testing in homes.”

The group found that clean cookstoves have the greatest potential to provide cleaner cooking solutions for households in low-to-mid-range incomes. Their findings are published on the Munk School of Global Affairs website.

Wong is thrilled to have been able to give the students a global experience: “The students are able to recognize that they can, in fact, make a difference,” he said. “There are careers to be made out of social innovations like this.”

Qaiser agreed. “I wanted a chance to apply my skills and learn to evaluate a health intervention in a real-world context, and I got to do just that. It was incredible.”

The students’ research received support from the Centre for Global Engineering, the Dean’s International Initiatives Fund at the Faculty of Arts & Science and the Asian Institute at the Munk School of Global Affairs.