Professor Shai Cohen recently joined the Institute for Studies in Transdisciplinary Engineering Education and Practice (ISTEP) as a faculty member. Cohen is a recognizable face for many U of T students and alumni, having taught in the Department of Mathematics, Computer Science, Rotman School of Management, and U of T Engineering, over the last 25 years.

“My first experience at U of T Engineering was when a professor blew out a ligament just a few days before the start of term. I was brought into the undergraduate chair’s office and asked if I wanted to teach a course that began in four days,” says Cohen. The following year, after another unforeseen circumstance, Cohen ended up teaching all four sections of a calculus course by himself.

“Somehow, teaching in Engineering always presents me with fascinating challenges, and it has been exhausting and delightful.”

Writer Liz Do spoke with Cohen to learn more about his teaching style and his goals as a new member of ISTEP.

Why did you choose to join ISTEP at U of T Engineering?

ISTEP was the natural place for me within the Faculty. I have taught every one of the first-year math courses for the Core 8 and Track One students. For several years, I have been working on improving the way we teach math to our students and the supports that we have for them to catch up on their studies. This is the best place for me to work with others who also focus on reaching multiple disciplines.

How would you describe your teaching philosophy?

The main idea behind it is that I believe in simultaneously challenging the students to perform at a level they did not think they could reach while supporting them in doing so. Throughout my career, I have seen how far students can go when no one tells them that they can’t, so I am aware that they can be driven to some remarkable achievements.

On the other hand, they also need to be given the tools to overcome any obstacles that lie in their path, whether it’s gaps in their foundational knowledge, learning disabilities, problems at home, or any other non-course related issue.

What do you hope to accomplish as an educator this term?

It’s the lockdown year, so I would be ecstatic with just getting my classes to the end of the term unscathed. I’ve been comparing this year to being a ship in a hurricane — the pilot in Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon comes to mind — we’re not aiming at any specific port; we’re just trying to stay afloat.

My biggest concern is my MAT 186T class, which is for students who dropped out of or failed calculus in the first semester. Fostering a sense of community and mutual support for this group will be a tall order, but absolutely essential.

What are your long-term plans or goals as an ISTEP faculty member?

I am looking to improve the way we teach mathematics for engineers. We are very good at teaching math and very good at teaching engineers. But putting these two things together — creating lessons that demonstrate mathematical principles in use with engineering concepts in a way that teaches both, getting instructors who are not trained in applied science to understand and teach these, and getting students to realize the use of such exercises — this is where I believe we should move in terms of our courses.

What are three things U of T Engineering students should know about you?

While I play an engineer on YouTube, where we have 500 videos for the online calculus courses, I do not have any formal training: just decades of watching my engineer father fixing things around the house and learning, from his creative cursing, the value of good design.

A lot of the students learn this eventually, but not enough: they can always ask me questions without having to be intimidated. It often seems like the biggest barrier for students to come to office hours is that the students are worried that I will “judge” them. Holding my hours in Sandford Fleming Atrium (before the pandemic) has certainly helped, but there are plenty of students who never show up to ask anything but should.

I’m almost never without a book nearby. If any student is looking for recommendations for reading material, I stand at the ready to give out a couple of dozen recommendations at the drop of a hat.

U of T Engineering remains Canada’s top-ranked engineering school and is now in the global top 20, according to the QS World University Rankings by Subject for 2021.

The rankings, released March 4, placed U of T Engineering 18th globally in the category of Engineering & Technology. This marks an increase from last year’s position of 22nd and the fourth consecutive year where the institution improved its ranking. Among North American public universities, our closest competitors, U of T Engineering now ranks 3rd.

“Our rankings and reputation are a direct result of the hard work and dedication of our community: faculty, staff, students, alumni and partners,” said Dean Chris Yip. “From the world-leading impact of our research to the richness of our student experience — including opportunities to develop leadership and global perspectives — we can all be proud of everything we do to shape the next generation of engineering talent.”

In terms of overall institution-level rankings, U of T placed 25th in the world. It also placed first in Canada in 30 out of the 48 specific subjects on which it was measured, and in the global top 10 internationally in areas ranging from education (third) to anatomy and physiology (sixth).

“This latest international subject ranking reflects the University of Toronto’s strength across a wide array of disciplines, from the humanities and social sciences to medicine and engineering,” said U of T President Meric Gertler.

“It is also a testament to our unyielding commitment to research, innovation and academic excellence.”

Quacquarelli Symonds evaluates universities by looking at five broad fields — Arts & Humanities, Engineering & Technology, Life Sciences & Medicine, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences & Management — and 51 specific subjects. The results are based on four measures: academic survey results, employer review survey results, citations per faculty and an index that attempts to measure both the productivity and impact of the published work of a scientist or scholar.

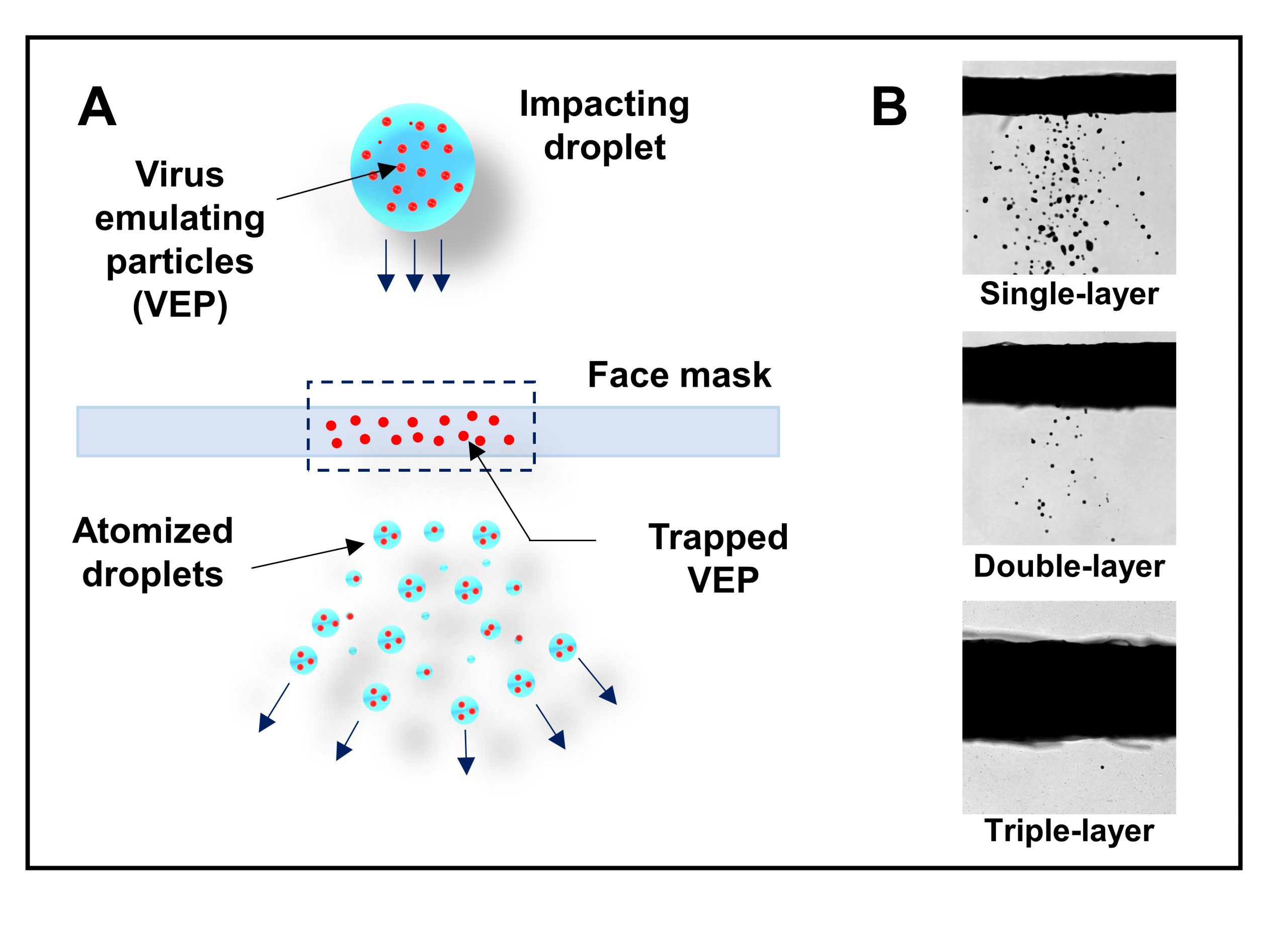

An experimental study carried out by an international team of engineers and physicists has added more evidence for the value of triple-layer masking to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and similar diseases.

“Any form of mask is better than no mask,” says Professor Swetaprovo Chaudhuri (UTIAS), one of the co-authors of a new paper published today in Science Advances.

“But what we also show is that if they have enough momentum, large liquid droplets can penetrate single or even double-layer masks. When they do, they break up into smaller droplets that are more persistent in the air.”

The team — which also includes Professor Abhishek Saha at the University of California San Diego, and Professor Saptarshi Basu of the Indian Institute of Science — is leveraging expertise they developed while studying aircraft engines. They use computer models and physical experiments to understand finely dispersed droplets in air, known as aerosols.

In two previous papers, the team used models to describe the ways that droplets and aerosols created by a cough or sneeze can travel and persist in air. These mechanisms were then incorporated to develop a disease spread model, the first one to be developed from the flow physics of transmission.

In the latest paper, they used a device known as a droplet dispenser to fire liquid droplets at a piece of material from single-, double- and triple-layer masks.

Learn more about the experiment in this video, created by the authors for the 73rd annual meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics. (Authors: Shubham Sharma, Roven Pinto, Abhishek Saha, Swetaprovo Chaudhuri, Saptarshi Basu)

The liquid used by the team was not real saliva but rather a facsimile made of water, salt and various proteins. The mask material was ordinary fabric with an average pore size of 30 micrometres, about the width of a human hair. Specialized cameras were used to take microscopic images up to 20,000 times per second to observe what happened.

“A pore size of 30 micrometres can easily stop large solid particles that aren’t travelling too fast, but liquid droplets are a different story,” says Chaudhuri. “Liquids can deform, and big droplets can break up into smaller droplets, which have different characteristics.”

Chaudhuri says that liquid droplets larger than 100 micrometres in diameter don’t usually spread very far, because they quickly drop to the ground via gravity. But droplets smaller than 100 micrometres wide form aerosols, which can persist in the air for much longer. The time period ranges from a few seconds in the case of those with diameters near 100 micrometres, to hundreds of hours for those near 10 micrometres.

The team’s experiments showed that when droplets larger than 250 micrometres were fired at a single layer mask, they atomized, breaking up into pieces small enough to penetrate the material and form aerosols. This also happened with double-layer masks, but the proportion of pieces that made it through was only about 9%, compared with about 70% with the single-layered mask. Triple-layer masks were enough to stop virtually all the droplets.

Chaudhuri is quick to point out that little is known about the fate of the aerosols created by the atomization process. More research is needed to determine whether they could carry enough viral material to be infectious or how far they could travel.

Still, the findings provide more experimental evidence for what public health agencies around the world are recommending: any mask is better than no mask, but the more layers, the better.

Furthermore, fitting and leakage are very important issues. “An N95 is best, but if that is not available, the latest recommendation is a cloth mask supplemented with a medical procedure mask,” says Chaudhuri. “The combined effect of procedural and well fitted cloth masks provide good filtration while reducing leakage”

While previous studies have looked at how droplets leak from the sides of masks, they typically have not captured how the mask itself can play a role in atomization.

“Most studies also don’t look at what is going on at the individual droplet level and how aerosols can be generated,” Basu adds.

This finding underlines the importance of a physics-based approach.

“When we study combustion and sprays and the turbulent flows involving them as in aircraft engines, we think about droplets and aerosols a lot, from a lot of different angles,” says Chaudhuri. “I think there’s great value in bringing these perspectives to bear on the challenge of COVID-19, which affects us all.”

An upgraded facility at U of T Engineering — one that is unique in the world — will let engineers test next-generation infrastructure designed to be resilient in the face of natural disasters, from hurricanes to earthquakes.

A grant announced today from CFI’s Innovation Fund 2020 will fund a suite of new tools and equipment to be housed within U of T Engineering’s existing Structural Testing Facility. They will be used to design everything from elevated highways to high-rise residential buildings to nuclear power plants, including replacements for legacy structures across North America.

“Much of our infrastructure is decades old and needs to be replaced,” says Professor Constantin Christopoulos (CivMin), the project leader and Canada Research Chair in Seismic Resilience of Infrastructure.

“The scientific and engineering communities, along with governments and the private sector, are becoming increasingly aware of the inherent vulnerability of our infrastructure. We also need to design new structures to address new pressures, such as a rapidly growing Canadian population, and more frequent extreme weather scenarios due to a changing climate.”

The centrepiece of this new development is the world’s first fully movable, adjustable multidirectional, large-scale and large-capacity loading frame.

“This unique piece of equipment will allow structural elements and structural systems to be tested under more realistic loading conditions,” says Christopoulos. “We’ll be able to better simulate the complex effects of extreme loading events, such as earthquakes, tornadoes, hurricanes or tsunamis.”

The adjustable, multi-dimensional loading module will be capable of applying up to a total of 2,000 tonnes of force in six translational and rotational directions for specimens of up to eight metres tall and thirty metres long.

The project will also include new state-of-the-art sensing equipment and the redesign of 500 square metres of lab space. Construction is expected to begin in 2022.

To make full use of it, Christopoulos will be working with a large team of experts from within and beyond U of T Engineering. Project partners include U of T Engineering professors Oh-Sung Kwon, Evan Bentz, Oya Mercan and Jeffrey Packer (all CivMin). This team is also collaborating with a team of structural engineering and large-scale testing experts at other leading North American facilities to develop, commission and use this unique equipment. Collaborating institutions include:

- Western University’s WindEEE and Boundary Layer Wind Tunnels

- University of British Columbia

- University of Sherbrooke

- Polytechnique Montreal

- University of Illinois

Once completed, the new facility will be used for research by 10 professors from U of T and their national and international collaborators. It is also expected that it will allow for dozens of unique graduate student research projects and industry tests every year once it is fully operational.

Together this team will be able to carry out a technique known as “distributed hybrid simulations.” This means that full-scale portions of real structures — such as concrete pillars or steel beams — will be tested simultaneously in each of these labs across North America.

By integrating all of these physical tests into a single numerical model, they can use the experimental feedback of each of the large-scale elements to more realistically simulate the response of the entire infrastructure system to extreme loading conditions. The data from the physical experiments will be integrated in real-time with models run using high-performance computers and the UT-SIM integration platform.

“This facility will enhance our capabilities not only here at U of T, and across Canada, but will position Canadian engineers as global leaders in the area of structural resilience” says Christopoulos. “It is a critical step toward designing the resilient cities of the future.”

Erin Richardson (Year 3 EngSci) was in Grade 9 when she decided she wanted to be an astronaut.

“We had a science unit on outer space, and I remember being completely fascinated by the vast scale of it all,” she says. “Thinking about how big the universe is, and how we’re just a tiny speck on a tiny planet, I knew I wanted to be part of exploring it.”

Richardson started following Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield on social media and watching videos of his daily life on the International Space Station. She also started reading about aerospace and doing everything she could to break into the industry, including getting her Student Pilot Permit.

It was in a Forbes article about women in STEM that she first read the name of Kristen Facciol (EngSci 0T9).

A U of T Engineering alumna, Facciol had worked as a systems engineer at Canadian space engineering firm MDA before moving on to the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). When Richardson first learned about her, Facciol was an Engineering Support Lead, providing real-time flight support during on-orbit operations and teaching courses to introduce astronauts and flight controllers to the ISS robotic systems. Today, Facciol is a Flight Controller for CSA/NASA.

“I found her contact information and reached out to her,” says Richardson. “She’s been an amazing mentor to me over the last five years. We’re still close friends, and she’s really helped influence my career path.”

With Facciol’s encouragement, Richardson applied to U of T’s Engineering Science program, eventually choosing the aerospace major. After her first year, she landed a summer research position in the lab of Professor Jonathan Kelly (UTIAS), working on simulation tools for a robotic mobile manipulator platform.

“Working in Kelly’s lab piqued my interest in robotics as they could be applied in space,” she says. “Researching collaborative manipulation in dynamic environments will push the boundaries of human spaceflight – during spacewalks, astronauts work right alongside robots all the time.”

After her second year, Richardson travelled to Tasmania for a research placement facilitated by EngSci’s ESROP Global program. Working with researchers at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia’s national science agency, she created tools to analyze data collected during scientific mooring deployments, which help us learn more about our oceans over long periods of time. This work informs the design of next-generation mooring systems which, like space systems, must survive harsh and constrained environments.

Richardson was sitting in a second-year lecture when she heard the news that Canada had committed to NASA’s Lunar Gateway project, a brand-new international space station set to be constructed between 2023 and 2026. Unlike the ISS, which currently orbits Earth, the Lunar Gateway will orbit the moon and will serve both as a waypoint for future crewed missions to the lunar surface and as preparation for missions to even more distant worlds, such as Mars.

Energized, Richardson searched for a way to get involved. Her opportunity came in the fall of 2019, when she saw a posting on MDA’s job board. She immediately applied through U of T Engineering’s Professional Experience Year Co-op program, which enables undergraduate students to spend up to 16 months working for leading firms worldwide before returning to finish their degree programs.

Richardson started her placement in May 2020, right in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. She and her employer quickly adapted.

“I was working from home through the summer, but for my latest project I was able to go onsite to operate this robotic arm,” she says.

The robotic arm in question is a model of Dextre, a versatile robot that maintains the International Space Station. Richardson used it as a prototype part for the Canadarm3, which will be installed on Lunar Gateway.

Because the Lunar Gateway will be so far from Earth, Canadarm3 will be designed to be autonomous, able to execute certain tasks without supervision from a remote control station. Part of Richardson’s job is to create the dataset that will eventually be used to train the artificial intelligence algorithms that will make this possible.

In MDA’s DREAMR lab, Richardson guided the robotic arm through a series of movements and scenarios, with a suite of video cameras tracking its every move. She then tagged each series of images with metadata that will teach the robot whether the movements it saw were desirable ones to emulate, or dangerous ones to avoid.

“We had to capture different lighting conditions and obstacles of various sizes and colours,” she says. “My colleagues pointed out to me that because it’s me deciding which scenarios count as collisions and which ones don’t, the AI that we eventually create will be a reflection of my own brain.”

Apart from the opportunity to contribute to the next generation of space robots, Richardson says she’s enjoyed the chance to apply what she’s learned in her classes, as well as the professional connections she’s made.

“It’s my dream job,” she says. “I use what I learned in engineering design courses every day. I’m treated as a full engineer and a member of the team. The people I work with are extremely supportive and they talk to me about my dreams and goals. I love being surrounded by a team of talented and motivated people, all so passionate about what they do and about advancing space exploration. It’s an awesome opportunity for any student.”

During the pandemic, Marie Floryan (MechE 1T9 + PEY) has been analyzing and comparing COVID-19 mitigation strategies in different countries around the world.

She worked on the side project while pursuing her master’s in mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Floryan was driven by a deep interest in studying global challenges — a passion sparked during her time at U of T Engineering.

In 2020, Floryan was selected as one of 25 recipients of the Engineering for Change (E4C) Fellowship. The fellowship, founded by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Engineers Without Borders (U.S.) and Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, aims to deepen engineering students’ and early-career engineers’ leadership and global development.

“The fellowship was a real deep dive into the global engineering space, and it’s been eye-opening,” says Floryan. “It expanded what I know about how engineers operate around the world. When I’m going about solving a design problem, I’m learning to think more about the stakeholders and how I should be engaging with them to get to the actual root of solving it.”

For the COVID-19 project, her E4C cohort studied how engineers responded to the pandemic in high-, medium- and low-income countries, with Floryan comparing mitigation strategies in Canada, the U.S. and Ghana.

“It was interesting to learn that, although the three countries had a lot of similarities in terms of government support, the progress was much quicker in Canada and the U.S. because the governments were able to provide the financial incentives more quickly,” explains Floryan. “Ghana had to rely more on private partners to get funding and are still reliant on the importation of certain products to fight the pandemic.”

The E4C Fellowship supports more than 400 hours of research, 30 hours of networking opportunities with peers and mentors, as well as 30 hours of learning modules designed to advance their knowledge in sectors such as health, transportation and agriculture.

Floryan says applying for the fellowship was the natural next step upon graduating from U of T Engineering, where she zeroed in on global engineering during her final year in mechanical engineering. Through the Centre for Global Engineering, she took courses on technology and global development, as well as designing a food-growing strategy for an Indigenous community in Northern Ontario.

For her fourth-year capstone project, her team worked with international disaster relief charity GlobalMedic (GM) to design a more efficient sandbagging machine for flood-prone areas. Their solution repurposed snowblowers with just a few cost-effective mechanical adjustments.

“One single ‘sandblower’ is able to produce at least 56 sandbags per hour, compared to the current standard of 12 sandbags per hour using shovels,” explains Floryan. “The work was very rewarding and what led me to explore global engineering further.”

In addition to her COVID-19 case study, E4C also provided her an opportunity to research products designed for low-resourced settings, studying how different engineers approached their solutions, from concept to manufacturing.

“There are so many design challenges that we just don’t have to think about in Canada,” says Floryan. “Sanitary pads, for example, is a product that is seen, in some communities, as taboo. This means certain design and distribution considerations must be applied to not only make them safe, but discreet.”

Though there is usually a travel component to the fellowship, Floryan has yet to go abroad due to the pandemic. She is hopeful to visit members of her cohort post-pandemic, and plans to apply her current graduate research — designing a microfluidic device to study cancer metastasis — to a global context.

“The world is becoming more connected and it’s important to shift our perspectives to think more globally as engineers,” says Floryan. “It’s our duty to think about how our actions affect the future and promote more positive, sustainable growth around the world.”