Angela Schoellig, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies (UTIAS), has been awarded a 2017 Sloan Research Fellowship. She will receive USD $60,000 over a two-year period to stimulate her fundamental research into machine learning as applied to autonomous aerial vehicles.

“This is both an incredible honour and very humbling,” said Schoellig. “It really is recognition of the work of my entire research group and all of my collaborators — both current and past. This award will enable us to focus on new exciting directions in the development of machine learning algorithms for robotics.”

The Sloan Research Fellowships are sponsored by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and are awarded in recognition of distinguished performance and a unique potential to make substantial contributions to their field.

Schoellig is one of only five researchers at Canadian universities out of the 126 early-career scholars honoured this year. She joins her U of T colleague Benjamin Rossman, an assistant professor of mathematics and computer science, as well as a number of her peers at institutions such as Princeton University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University.

“U of T congratulates our researchers on receiving this prestigious North America-wide award,” said Vivek Goel, U of T’s vice-president of research and innovation. “We’d also like to thank the Sloan Foundation for once again recognizing and supporting the excellence of U of T scholars of outstanding promise.”

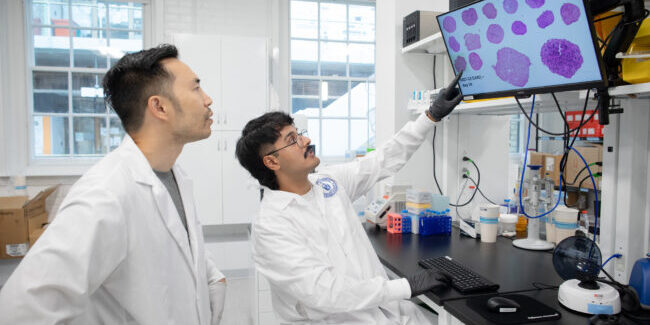

Schoellig, who heads the university’s Dynamic Systems Lab and is associate director of the Centre for Aerial Robotics Research and Education (CARRE), conducts research combining robotics, controls and machine learning. Her goal is to enhance the performance and autonomy of robots by enabling them to learn from past experiments and from each other.

Learn more about Professor Schoellig’s research and outreach activities at U of T Engineering

For example, researchers can’t program an autonomous vehicle, like a self-driving car, for every possible weather condition. “We can’t replicate them all in the lab,” she said. Instead, they can program the vehicle to react cautiously in an unknown situation and learn from each new experience accordingly. Safety is their number one priority.

She has been working with aerial vehicles for the past nine years and more recently has applied her motion planning, control and learning algorithms to outdoor ground vehicles. As expected, she says the algorithms that work for flight, transfer well to driving.

Interest in her field has exploded in the past six to seven years, she said, recalling when she did her PhD finding funding for robotics research and development was difficult but “now it’s a complete change” as automotive and tech companies race to lead this emerging field.

The flying robots designed by Schoellig and her team could be adapted to many tasks, from monitoring pollutants in remote lakes to delivering automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) rapidly and directly to homes. However, there is much to be done before flying robots can take on these tasks in a robust, dependable way.

“It’s always a concern that the technology is being oversold,” she said, noting the excitement each advancement in autonomous vehicles receives by the media and corporations. “But as researchers, we know and understand the limitations of the technology.”