Microplastics exist all around us — in the water we drink, the food we eat and the air we breathe. But before researchers can understand the real impact of these particles, they need faster and more effective ways to quantify what is there.

Two recent U of T Engineering studies have proposed new methods that use machine learning to make the process of counting and classifying microplastics easier, faster and more affordable.

“It’s really time consuming to analyze a water sample for microplastics,” says Professor Elodie Passeport (CivMin, ChemE).

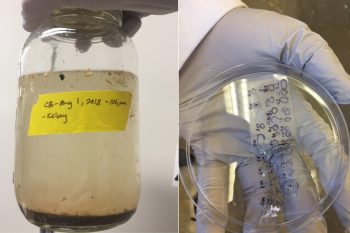

“It can take up to 40 hours to fully analyze a sample the size of a mason jar — and that specimen is from one point in time. It becomes especially difficult when you want to make comparisons over time or observe samples from different bodies of water.”

This past March, the United Nations Environment Programme endorsed a historic resolution to end plastic pollution, which it called “a catastrophe in the making,” due to the threat the production and pollution poses to human health, marine and costal species, and global ecosystems.

The synthetic material can take hundreds to thousands of years to biodegrade. But it is not just visible plastic refuse that is an issue: over time plastic breaks down into smaller and smaller particles. Those pieces that are less than five millimetres in size but greater than 0.1 micrometres are defined as microplastics.

Researchers who study the effects of microplastics are still trying to understand how these tiny pieces could affect human and environmental health in ways that are different from the bulk material.

Though past studies have demonstrated the presence of microplastics in various environments, the standards for how to quantify their levels — and critically, how to compare different samples over time and space — are still emerging. Passeport worked with PhD student Shuyao Tan (ChemE) and Professor Joshua Taylor (ECE) to address the challenge of analysis.

“We asked ourselves whether there could be a crude measurement that could predict the concentration of microplastics,” says Passeport.

“In collaboration with Professor Taylor, who has expertise in machine learning and optimization, we established a prediction model that employs a trained algorithm that can estimate microplastic counts from aggregate mass measurements.”

“Our method has guaranteed error tracking properties with similar results to manual counting, but it’s less costly and faster, allowing for the analysis of multiple samples from multiple points to estimate microplastic pollution.”

The team’s investigation, published earlier this year in ACS ES&T Water, has the advantage of allowing researchers to manually process only a fraction of their collected samples and predict the quantity of the rest using an algorithm, without introducing any more error or variance.

“Researchers working on microplastic analysis need to know how many plastic particles there are, the kinds of particles, the polymers and shapes,” says Tan.

“With this information, they can then study the effects of microplastic pollution on living organisms — as well as where this pollution is coming from, so they can deal with it at the source.”

Classical quantification methods using visible light microscopy require the use of tweezers to count samples one-by-one under an optical microscope — a labour-intensive endeavour that is prone to human error.

In an investigation published in Science of The Total Environment, PhD candidate Bin Shi (MSE), who is supervised by Professor Jane Howe (MSE, ChemE), employed deep learning models for the automatic quantification and classification of microplastics.

Shi used scanning electron microscopes to segment images of microplastics and classify their shapes. When compared to visual screening methods, this approach provided a greater depth of field and finer surface detail that can prevent false identification of small and transparent plastic particles.

“Deep learning allows our approach to speed up the quantification of microplastics, especially since we had to remove other materials that could create false identifications, such as minerals, substrate, organic matter and organisms,” says Shi.

“We were able to develop accurate algorithms that can effectively quantify and classify the objects in such complex environments.”

It is this diversity in the chemical composition and shapes of microplastics that can create difficulties for many researchers, especially since there is no standardized method to quantify microplastics.

Shi collected microplastic samples in various shapes and chemical compositions — such as beads, films, fibres, foams and fragments — from sources including face wash, plastic bottles, foam cups, washing and drying machines, and medical masks. He then processed images of the individual samples using the scanning electron microscope to create a library of hundreds of images.

This project is the first labelled open-source dataset for microplastics image segmentation, which allows researchers from all over the world to benefit from this new method and develop their own algorithms specific to their research interests.

“This method also has the potential to go down to the scale of nanoplastics, which are particles smaller than 0.1 micrometres,” says Shi.

“If we can continue to expand our library of images to include more microplastic samples from different environments with varied shapes and morphologies, we can monitor and analyze microplastic pollution much more effectively.”

For now, the goal of Passeport and Tan’s predictive model is to be a diagnostic tool that can help researchers identify areas where they should concentrate their analytical efforts with more in-depth technologies.

The team also hopes this method can empower citizen scientists to monitor microplastic pollution in their own environments.

“Individuals can collect samples, filter and dry them to get the weight and then use a trained algorithm to predict the amount of microplastics,” says Passeport.

“As we continue our work, we want to introduce some automatic training sample selection methods that will allow individuals to just click a button and automatically select the training sample,” adds Tan.

“We want to make our method easy so that they can be used by anyone, without them needing any knowledge of machine learning and mathematics.”